Three million Australians have now applied to the Super Early Release Scheme, with $30 billion already paid out and more than 500,000 members emptying their accounts. Harry Chemay takes a look at the nation’s retirement system, which costs 10 times more to run than the Tax Office and has enabled the highly paid to accelerate their wealth precipitously.

If superannuation didn’t exist, and you went to the Treasurer of the day proposing a retirement system that would require 10 times the operating cost of running the Australian Taxation Office but wouldn’t deliver a net benefit to the Commonwealth budget for at least 50 years, you’d get short shrift.

If you further proposed that same retirement system primarily be a vehicle for the highly paid to supercharge their accumulation of wealth through tax concessions worth some $36 billion each year, you’d probably be expected to be shown the door.

But this is the system we have ended up with today, nearly 30 years on from Paul Keating’s defining speech outlining his vision for Australia’s retirement system.

The annual cost of administering the super system, and investing for the nation’s 16 million account holders, is in the order of $32 billion.

The ATO runs on the smell of an oily rag by comparison – with an annual budget of about $3.4 billion, a tenth of the super industry. On that budget the Tax Office oversees the tax affairs of 12 million individuals, 4.2 million small businesses, 865,000 employers, 36,000 large multinational entities, 35,000 registered tax agents, 201,000 not-for-profits and all self-managed superannuation funds (SMSFs).

Either the ATO is comically underfunded, or the super industry is obesely inefficient. Very possibly both.

Back where it all started

On a cold July day in 1991, Paul Keating strode to the front of the Australian Graduate School of Management’s lecture theatre at the University of New South Wales.

The MBA students were in for a treat. What they were about to hear would benefit them directly, career-wise and financially, although none could have known it at the time.

Keating was giving the address as a backbencher, having lost a leadership ballot to prime minister Bob Hawke a month earlier.

It was not a position the man once dubbed “The World’s Greatest Treasurer” was keen to get used to. He had a grander vision, for himself and for future retirees.

The speech was a key plank in that vision, and he aimed to make it count.

Policy shaped the nation

It did, and by December Keating was prime minister. Much of what he outlined in that speech has come to pass, shaping the Australia of today in a way few policies have done since.

While the Prices and Incomes Accords of the mid-to-late 1980s had delivered superannuation, at the rate of 3%, to 85% of awards, only 64% of workers were covered, most of whom were in the public sector.

As Keating saw it, 3% was far from sufficient. His goal was that “by the year 2000 every employee has a contribution to superannuation equal to 12% of wage and salary income paid into (their) superannuation account”.

Keating’s vision was a compulsory contributory system where a portion of nearly every working Australian’s wages would be directed into a personal superannuation account.

The Superannuation Guarantee system came into effect on July 1, 1992, but the 12% rate has been the subject of intense political debate ever since. The rate is currently legislated to rise half a per cent to 10% on July 1, 2021, before reaching Keating’s target on July 1, 2025, some 25 years overdue.

A growing chorus is now arguing for that half a per cent rise to be directed into wage rises instead, to prioritise take-home income in a Covid-19 ravished economy. The Government, meanwhile, sits on a Treasury Retirement Income Review report, widely thought to have a view on the matter.

A $3 trillion national leviathan

The wheels Keating set in motion that July day turned a then $140 billion minnow into a current $2.7 trillion financial leviathan. The nation’s retirement pool, already 140% greater than the nation’s annual GDP, is projected to rise to 190% by 2038.

The system feeds on $120 billion in annual contributions, 80% via employer payments.

Super is dominated by a handful of large funds regulated by the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority, accounting for $1.9 trillion of assets.

Between these funds lies a philosophical chasm, with 36 profit-to-member-funds (“industry funds”) on one side, and 110 bank and institutionally owned retail funds on the other.

Some 600,000 SMSFs, collectively accounting for $670 billion in assets, together with an assortment of public, corporate and statutory funds round out the super system.

The scale of assets in superannuation is best illustrated by the fact that while the nation’s population is just 25 million people, we have the fourth largest retirement pool, behind the US, the UK and Japan.

Inordinately expensive to run

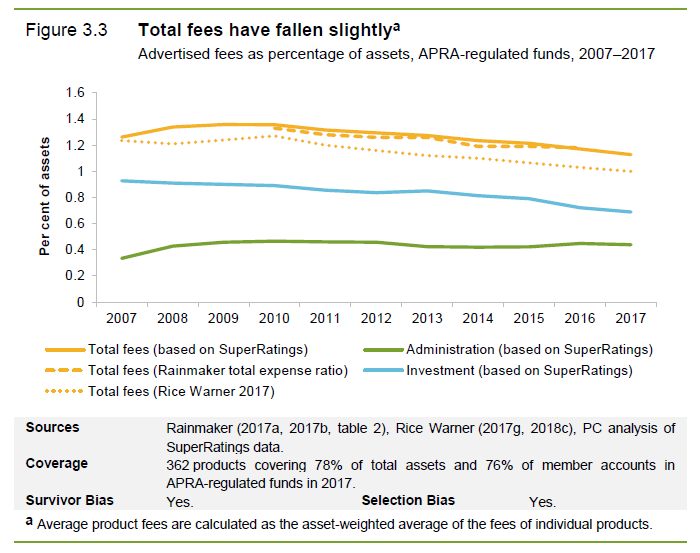

As noted earlier, super appears to be an inordinately expensive pool of assets to maintain. The direct cost to members is estimated at about $32 billion a year – 1.1% of account balances, plus annual insurance premiums of some $9 billion.

These costs appear remarkably resistant to the benefits of scale, as the chart from the 2017/18 Productivity Commission review into super indicates:

The $32 billion in charges pays for account administration, custody of assets, investment management and various governance, audit and assurance operations surrounding it.

All aboard the gravy train

Keating’s superannuation dream within a privatised system has spawned an industry now directly employing some 55,000 comparatively well-remunerated individuals.

In addition, an army of service providers exist to cater to the funds, encompassing fund administrators, asset managers, custodians, registries, data analytic companies and member engagement agencies, together with lawyers, consultants and audit/assurance professionals all engaged to keep fund trustees on the right side of a hugely complex legislative edifice. Then there are some 20,000 financial planners.

Collectively, all these roles account for a significant slice of some 450,000 finance jobs, making financial services the largest employing industry in Australia.

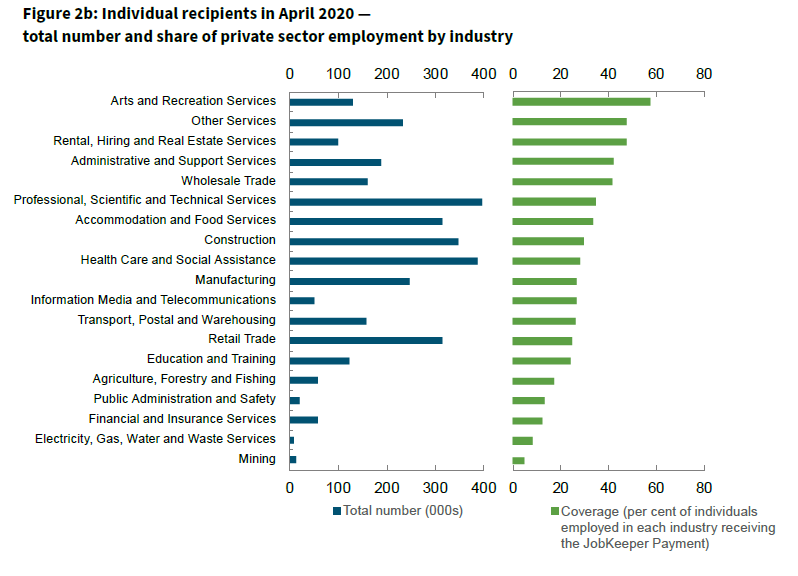

It has also been relatively sheltered from the Covid-19 crisis, with a Treasury review of JobKeeper recipients noting that, while the arts, recreation and related sectors were haemorrhaging jobs, financial and insurance services were among the sectors least affected.

Regressive taxation 101

Superannuation has been an absolute boon for the highly paid to turbocharge their accumulation of wealth. Those bright young MBA candidates would doubtlessly have proceeded to high-earning careers, many in financial services.

They would have had ample opportunity to take advantage of a raft of super tax concessions – the cost of which exceeds $36 billion annually. Many would also be approaching the golden age of 60, when paying tax becomes broadly optional, with the flows more commonly reversed.

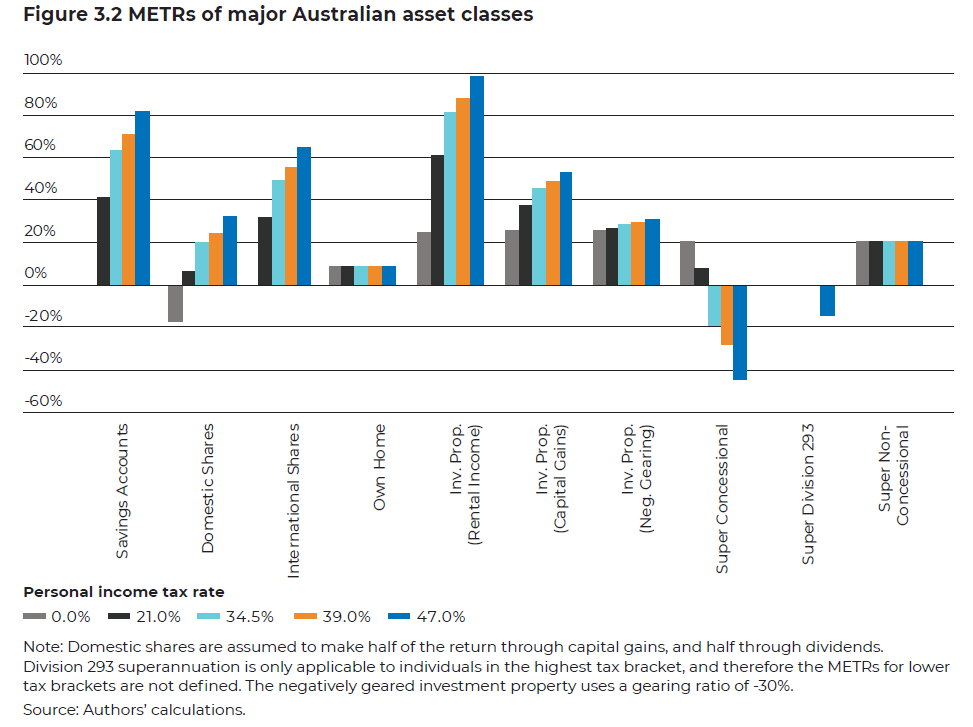

As a recent study by the Tax and Transfer Policy Institute reveals, much of the tax benefit of super flows to higher income and older, wealthier Australians. In ‘The Taxation of Savings in Australia: Theory, Current Practice and Future Directions’, the TTPI analysed effective tax rates for different marginal taxpayers.

The largest tax advantage for higher income earners building wealth is achieved through concessional super contributions, as the below chart depicts.

And the huge benefit of franked dividends for wealthy over-60 retirees featured heavily in last year’s federal election campaign.

Almost 30 years on, Paul Keating’s creation has never been more significant, or more partisan. Superannuation divides people trenchantly down party political lines. Those on the left hold super sacrosanct; a legacy for the ages. Those on the right remain suspicious of super’s ‘true intent’, certain that its nefarious aim is to erode personal freedoms and facilitate the resurrection of union militantism.

Neither position stands up to detailed scrutiny, but this much is assured. It should, by now, be abundantly clear to policymakers that this current level of taxpayer largesse is simply unsustainable.

Emergency piggy-bank: superannuation’s Achilles heel exposed by virus

Harry Chemay has more than two decades of experience across both wealth management and institutional asset consulting. An active participant within the wealth and superannuation space, Harry is a regular contributor to investment websites in Australia and overseas, writing on investing and financial planning.