In “Triskele’s” earlier report, the Murray-Darling Basin Plan is described as a tragi-comedy in three acts (and a prologue). The subtext was the stench of influence-peddling, cronyism, regulatory capture, conflicts of interest and who and what our political leaders and bureaucrats have been defending or representing. In this piece, Triskele reviews the performance of the Murray-Darling Basin Authority (the MDBA), a central actor in the Murray-Darling Basin Plan (the Plan), and the central actor in the South Australian Murray-Darling Basin Royal Commission Report.

Knights of the Round Table

The MDBA began its life in 2007 cast as a central actor in a truly visionary, world’s-best-practice system of water governance. Under the aegis of the Water Act 2007 and the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, the MDBA was the statutory authority responsible for preparing, implementing, monitoring the Basin Plan, and providing independent information and technical advice to governments about it. It was as a sort of bureaucratic Knight of the Round Table.

In the space of a few years, it metamorphosed into something more resembling Monty Python’s Black Knight.

Monty Python’s Black Knight (image courtesy https://villains.fandom.com)

Predictably, the biggest blows to its image were inflicted by the South Australian Murray-Darling Basin Royal Commission Report (the Royal Commission Report) of January 2019. The Royal Commission Report deserves to be read. It is elegantly written prose, exceptionally clear, and completely devoid of bureaucratese. The beauty of its execution contrasts painfully with the ugliness of much of its findings.

The Commissioner found the MDBA to be negligent; acting in dereliction of its duties; showing deplorable judgement; “unwilling or incapable of acting lawfully”, and habitually behaving in a way “marked by an unfathomable predilection for secrecy.” He also found that the Basin Plan is not being implemented in a cost-effective manner; is not in accordance with the best science and practice; is not engaged in adequate consultation with affected communities; nor is even in proper compliance with the Water Act.

Put baldly, the MDBA was found to be acting not in compliance with the Water Act, because it was acting politically. It could not do its job properly because it set itself the political objective of keeping all the states and the Commonwealth in the tent as its principal objective. In setting the Environmentally Sustainable Level of Take (ESLT) and thus the Sustainable Diversion Limit (SDL – the amount of environmental water that must be returned to the river – both the MDBA and the Commonwealth government have failed to follow the requirements of the Water Act, resulting in a major failure of process.

As the Commissioner put it:

“Instead of trying to fix the limit beyond which key environmental values would be compromised, they appear to have set out to gauge the limit of sectional or political tolerance for a recovery amount. The story of this cynical disregard for the clear statutory framework for decision-making on this crucial measure is unedifying, to the lasting discredit of all those who manipulated the processes to this end.”

The prioritising of political objectives has therefore led to unlawful derivation of the environmental targets that the Plan was supposed to meet:

“Politics rather than science ultimately drove the setting of the Basin-wide SDL and the recovery figure of 2750 GL. The recovery amount had to start with a ‘2’. This was not a scientific determination, but one made by senior management and the Board of the MDBA. It is an unlawful approach. It is maladministration.”

The MDBA has interpreted the Water Act in such a way as to defend an entirely mythical “triple bottom line” which served to put economic, social and environmental outcomes on the same level of importance, if not indeed prioritising the first two. The “triple bottom line” was described by the Commissioner as little more than a publicity slogan. Crucially, by impermissibly interpreting the Water Act in this way, the MDBA has infected the whole process of setting up an ESLT, and consequently the SDL.

It did this reliant on that one piece of Australian Government Solicitor advice, which the Commissioner says “is almost certainly inconsistent with prior advice to the MDBA or the Commonwealth on the construction issue”, but which curiously the Commonwealth Government and MDBA refused to make available to the Royal Commission, and still refuse to release publicly now. If this crucial piece of legal advice is found to be incorrect, the whole triple-bottom-line house of cards would collapse.

The MDBA has also relied on a spurious interpretation of what the word “compromise” means in the legislation in order to reach exactly the opposite understanding of what the Act intends (which is to avoid compromising – or prejudicing – the environmental needs of the river system, as opposed to reaching a mutually agreeable settlement between economic, social and environmental needs).

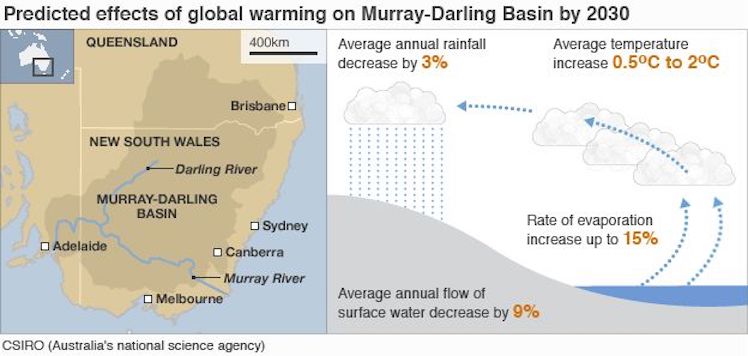

In order to defend this triple bottom line, the MDBA has ignored, sidelined and even censored science that undermined achieving this end goal and has also minimised attention to the issue of climate change and its potential impacts.

Logically, in order to get the Basin Plan back on track, we would need to revisit the ESLT and the SDL; revisit the mechanisms by which we can get to the new targets; and address the serious resourcing deficiencies and the governance issues affecting all areas of the MDBP, including its central actor, the MDBA. These issues are the core of the Commissioner’s recommendations. All of them are rejected by the MDBA, with the exception of increasing resourcing in some areas.

#Australia hottest summer on record and it's longest rivers are drying up. The #WaterShortage is destroying wildlife, #aboriginal communities and farming in the #MurrayDarling basin. Who's to blame for the #drought ?

World; https://t.co/QplYlckDhE pic.twitter.com/AyCe0hG2PL— BBC Our World (@BBCOurWorld) March 17, 2019

Stage Right: The Black Knight enters

As I have described earlier, the MDBA very obviously changed tack from 2010, in response to the buckling of the minority Gillard government, which introduced the concept of the triple-bottom-line, and under pressure from the LNP governments since 2013, which adopted an actively anti-environmental and pro-irrigator agenda.

The MDBA became acutely sensitive to the change in direction around the politics of water, and its performance fell into line with what was expected of it by its political masters. We can see the scale of this co-option in the defensive reaction to the Royal Commission report. The MDBA’s formal response to the Royal Commission recommendations was to deny and disagree with almost everything. It denies it is incompetent, negligent, or opaque. Its mantra is that it is faithfully performing its duties in transparent fashion consistent with the Water Act. It argues that the Commissioner has presented no evidence to substantiate his claims; or that his report is based on the claims of heavily selected testimonies; or that he just doesn’t get it. Occasionally, it deflects responsibility by effectively throwing the CSIRO under the bus.

The MDBA appears to agree with the Commissioner’s findings only where these relate to the need for extra funding, or are obvious motherhood statements (such as increased Indigenous participation in consultation), without addressing how this would be done. Tellingly, the MDBA rejects addressing a key recommendation – the re-deliberation of the ESLT and the SDL – because it would mean starting the plan (and therefore, the political chaos) again, which it considers a “reckless act”. The MDBA did not agree with the Commissioner’s recommendation that the crucial piece of Australian Government Solicitor’s advice about the “triple bottom line” be released, but its bureaucratese rebuttal to the Commissioner offers no insight into why.

There is a key difficulty with the defensive approach taken by the MDBA, namely that the MDBA could have clarified or refuted the mass of evidence that stands against it in the forensic 758 page report, as it was consistently and publicly encouraged to do, at the actual Royal Commission. Instead, it took the Commissioner to the High Court in order to avoid being forced to appear and refused to meet the Commissioner, alleging it was “too busy”. The MDBA’s “Asio-like”secrecy quite reasonably induces sensible people to infer that this game of Scarlet Pimpernel can only be the result of political pressure.

The Black Knight: governmental human shield

Phillip Glyde

Interestingly, the MDBA also firmly rejected the Commissioner’s recommendation to separate out its regulatory and support roles and reform water governance. It is not clear why the MDBA feels it is inside its remit to take clear positions on some issues, like this one, and not others. For example, in February 2016, the current Chair Phillip Glyde was reported to have said that any decision about pausing the Plan, changing its timeline for implementation, or any other change, was a political decision, and outside the authority’s remit.

The MDBA’s stance is certainly not supported by the Productivity Commission, which is responsible for monitoring the MDBA’s performance since Abbott abolished the National Water Commission. In its Murray-Darling Basin Plan: Five Year assessment (December 2018) the Productivity Commission noted in carefully calibrated but nevertheless crystal clear language, that the only way to secure confidence in the Plan and spend the remaining $4.5 billion earmarked for the Plan effectively would be if the Basin governments focused on good governance. It noted that “It is unclear who is responsible and accountable for leading the implementation of the Basin Plan — the MDBA or Basin Governments.” It found that the MDBA played a key role in developing the Plan and amendments to it; but since 2012, there has been an implicit shift towards the MDBA seemingly leading the implementation of the Plan, and

“stakeholders most often perceive it to be an Authority that is in charge (although of what is unclear). Basin Governments have not sought to challenge this position, or explicitly claim this role.”

In other words, given the politically contentious nature of water politics, Basin governments have allowed the MDBA to be their human shield.

In its response to the Productivity Commission’s draft report on the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, which had already flagged serious institutional and governance shortcomings, the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources took a “move-along-nothing-to-see-here” attitude.

But in its final report, the Productivity Commission was unconvinced by this, pithily noting: “Reform is required”. Of the MDBA, it states:

“Governments have put it in an impossible position – it is an inherently conflicted entity and is perceived as such by stakeholders…. In its current form, the MDBA cannot be a trusted adviser to Basin Governments and a credible regulator.”

It finds that:

“Only complete structural separation would create incentives for each institution to pursue its functions more effectively, as well as develop the internal cultures most appropriate for the delivery of these functions”.

It recommends interim measures be put in place immediately, with the full reforms should be in place by 2021.

“It’s only a flesh wound”

The blows to the MBDA are various; and they’re heavy. Firstly, environmental and cost shortcomings — the Black Knight’s right arm.

There is something surreal about Glyde being quoted in November 2017 in an interview in CEO magazine chirpily stating that if we stick to the Plan, in 2024 there will be a return of wetlands and fewer endangered species:

“I mean, we’re already seeing silver and golden perch bouncing back because two-thirds of the surface water (more than 2,000 gigalitres) that is needed to get back to our sustainable level has already been recovered”.

But that was before the drama of the Menindee fish kills. It was before the report by the Australian Academy of Science, which found the kills are due to low flows caused by upstream extraction, exacerbated by drought. It was before the Australian National University study, which claimed that the government is grossly overstating the amount of environmental water that is being returned to the Murray-Darling Basin. It was before the Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists study on Water Flows in the Murray-Darling: Observed versus Expected, which found water flows down the system are possibly worse than they were before the Plan. The A$4billion (of the total spend of A$6billion) that has been spent – possibly squandered – to subsidise irrigation infrastructure (as opposed to voluntary water buybacks) is under serious scrutiny. The lack of water accounting of floodplain harvesting is also emerging as a hot button issue, and has led South Riverina irrigators to split from the NSW irrigators’ peak body.

Floodplain Harvesting is a huge economic black hole just waiting to happen to the tune of BILLIONS and not accounted for in the budget. Gross economic maladministration courtesy of the LNP. #politicalfix @anyonebutnats @Wyymj @MaryanneSlatte1 pic.twitter.com/fMi6Cfg559

— Justine Bucknell (@djbuck99) March 13, 2019

Despite all the government and MDBA studies, the public fear is that the Murray-Darling is in a state of collapse and deteriorating fast. Nothing produced by the MDBA or the Basin governments seems capable of alleviating that fear or addressing public mistrust. As Nick Feik in The Saturday Paper notes,

“Each year, the MDBA and state water agencies produce reports that run to thousands of pages, but they lack information in key areas. To read through them is to face the question of whether their function is not to manage the fair sharing of water but to provide cover for the outrage that is occurring.”

The MDBA is also crucially failing to deliver on public trust and confidence- and this is a blow to its heart.

CEO Phillip Glyde has overstepped his remit, revealing his political puppet status and continuing his lies about the state of the Basin.

Enough bs, heads must roll#whereistheriverdarling@greensjeremy @JohnEClements @MaryanneSlatte1 @Wyymj @modica4mallee https://t.co/LQLeU5gKlA— ??Jane MacAllister (@JaneMacallister) March 11, 2019

The MDBA is a statutory authority, and ostensibly is meant to be independent and at arm’s length from government. The perception of independence, however, is not aided by the fact that board members are named by the Federal Government. The second Chair, the former Labor member in the NSW parliament, Craig Knowles, became Chair in 2011, appointed by Tony Burke. The Liberal-appointed Chair from 2015, Neil Andrew, was a former Liberal MP for South Australia in the House of Representatives.

During his time as Minister of Agriculture and Water Resources, consistent with his policy of diluting anything spelling out the word “ecology” from the Plan and from the MDBA, Barnaby Joyce’s choices for the board were closely aligned with big irrigator interests. His appointment for the CEO of the MDBA was Phillip Glyde, who was warmly welcomed by the the National Irrigators’ Council. Its chief executive, Tom Chesson, said he believed Mr Glyde “has the experience within the resources sector to be able to bring a pragmatic approach to the MDBA’s work and hit the ground running.”

In 2017, Joyce nominated the Nationals’ number one NSW candidate for the Senate and irrigation lobbyist, Perin Davey, for the board, but the nomination was withdrawn after she was identified as being the voice in the Four Corners Episode Pumped, responding to disgraced NSW water regulator Gavin Hanlon’s offer of confidential information to irrigation lobbyists with the words “That’d be great. Thanks”. Davey had been an executive at Murray Irrigation, Australia’s largest irrigation company, and was on the board of the New South Wales Irrigator’s Council from 2014-2016 (and current policy manager).

Joyce’s successful appointments to the board were George Warne and Susan Madden. Warne is closely connected with big irrigator and irrigation infrastructure interests. He was the former CEO of Murray Irrigation Ltd, one of the largest irrigation corporations in the Murray Darling Basin, as well as CEO of State Water NSW, and Interim CEO of the Irrigation Renewal Program. In 2018, Murray Irrigation Ltd was found to have breached water charging rules by the ACCC, although the matter was resolved administratively.

Madden is an agricultural economist and a former EO of Macquarie Food and Fibre, which represents irrigators in the NSW Macquarie Valley. These irrigators have been associated with free-for-all floodwater harvesting of waters for cotton production.

One of the only parts of the Macquarie Marshes which still has water. Photo courtesy of ABC News’ Matthew Abbott.

These two board appointments were replacements for emeritus professor and water scientist Barry Hart of Monash University, and Di Davidson, an agricultural scientist and horticulturalist. While they did not attract the level of controversy that Davey’s proposed nomination attracted, both represent a shift towards greater representation of major corporative irrigator interests.

Following the expiration of the term of Neil Andrew as Chair of the MDBA, there is a current Acting Chair at the MDBA, while the government appoints a new Chair. The new Chair is being appointed at an even more delicate and sensitive moment than in 2010, where arguably the process of the MDBA’s politicisation began. In the wake of recent reports about the political stacking of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal; jobs-for-the-boys diplomatic roles; and the puzzling spectacles of “captain’s pick” naming of new Chairs of the ABC, these cosy appointments reasonably raise the spectre of revolving doors and Game of Mates. It is reasonable that such a politically sensitive role be kept miles away from any perception of possible conflicts of interest or co-option, particularly given the scandal of regulatory capture of the NSW water regulator. This ought to be the case even if the conflicting roles of the MDBA are finally separated. It is worth mentioning here the well-respected National Water Commission, abolished by Tony Abbott, which used to be responsible for the monitoring, audit and evaluation of the National Water Initiative. Its Commissioners represented the Commonwealth Government and all the Basin States, but were expressly to be independent, and not representative of any jurisdiction or industry sector. Its membership also made it much less susceptible to Federal Government influence.

Meanwhile, in what could only be described as a blow to the groin if it actually happens, Craig Wilkins of the SA Conservation Council told the Senate Inquiry into repealing the 1500 gigaliter limit on government water buybacks that a legal challenge to the Australian Government Solicitor’s advice (which is the legal underpinning to the concept of the triple-bottom-line) was under consideration. Of course, there is also the possibility that someone might put in a Freedom of Information request, to ferret out that advice, and also whatever other pieces of legal advice the MDBA might have received and chosen to disregard.

The final dismemberment could yet proceed from a Federal Royal Commission, if this is called. This has been supported by the Greens, and if held, it would flush out all the Commonwealth and State bureaucrats who were blocked by their respective governments from speaking to the SA Royal Commissioner.

Structural changes and further investigations seem inevitable. On 29 November 2018, the Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee released a report on the integrity of the water market in the Murray-Darling Basin, one of whose key concerns was the lack of confidence in the MDBA’s independence. During the last sitting week of parliament, S.A. Senator Tim Storer put forward a motion calling on the government to implement all of the recommendations of the Royal Commission and the Productivity Commission, including a push for the structural separation of the MBDA — a measure which has the support of the ALP. Federal Labor has asked for an investigation by the Commonwealth Public Service Commission (though this is unlikely to eventuate).

This week, the dismemberment of the MDBA has moved from the metaphorical to the real. David Littleproud has just announced that 103 of the Authority’s jobs would be moved to Mildura, Griffith, Murray Bridge, and Goondiwindi, as part of the Nationals’ decentralisation policy. This is up from the current 27 jobs and will mean that one third of the MDBA staff will be based in the regions. The relocation of jobs has been touted as a boost to local economies, and “will give the MDBA a better understanding of challenges and emerging threats.” Given that another loud and frequent criticism made of the MDBA is around its largely tokenistic processes of community consultation, a physical presence close to major agricultural centres could be a step in the right direction. However, the dust from the relocation of the Australian Pesticides and Medical Veterinary Authority relocation to Armidale, which I have earlier written about, has not yet settled.

It is fair to ask whether relocating MDBA staff at just this time is not ill-advised, and whether it is a case of image and crisis management by the National Party, and yet another case of policy on the run. It also begs the question of what challenges and emerging threats the MDBA has failed to grasp until now.

Exit stage left

The MDBA may still see itself as a Knight of the Round Table, but it has effectively morphed into the Black Knight. It may be true that the Plan is still worth defending and should be defended, but the question still remains whether, despite best intentions, the MDBA is capable of fulfilling its statutory role. The need to defend the current political and institutional arrangements at any cost seems to lead the MDBA to inhabit a parallel universe. It obsessively defers to the mantra of delivering the Plan “in full and on time” — a mantra that the Royal Commissioner found to be essentially an arbitrary and vacuous slogan; and timelines which the Productivity Commission also found cannot, and should not, be met. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that even now, the MDBA is desperately trying to keep everyone inside the tent and save the Basin Plan in its current form even as the Plan is put under such pressure as to render its central objectives impossible to achieve and therefore meaningless. As Senator Rex Patrick astutely noted in Senate Estimates: “The plan is a means to an end, not the end in itself.”

The other main actors in this spectacle however – namely the Commonwealth and Basin State governments – have put in a performance at least as appalling as the MDBA. It is to them that I turn in the next review.

——————-

The above investigation is published anonymously at the author’s request. “Triskele’s” identity and bona fides are known to us. “Triskele”  is an academic and journal editor as well as independent researcher interested in politics, history, current affairs, books, languages, and “all things nerdy”.

is an academic and journal editor as well as independent researcher interested in politics, history, current affairs, books, languages, and “all things nerdy”.

Public support is vital so this website can continue to fund investigations and publish stories which speak truth to power. Please subscribe for the free newsletter, share stories on social media and, if you can afford it, tip in $5 a month.

The above investigation is published anonymously at the author’s request. Triskele’s identity and bona fides are known to us. Triskele is an academic and journal editor as well as independent researcher interested in politics, history, current affairs, books, languages, and “all things nerdy”.