“A fraud on the environment” is how lawyers for the Royal Commission framed it. Cronyism, cover-ups, deception, secrecy, scientists “leaned on”. The Murray-Darling Basin Royal Commission report is to be handed down in little over a month and the outcome, for Australia’s water authorities, will not be pretty. Triskele reports – in a tragi-comedy in three acts – on the extraordinary events surrounding Australia’s most critical inland water system.

Act One: The Drama

The Murray-Darling Basin Royal Commission was announced in November 2017 to investigate allegations that upstream irrigators were stealing billions of litres of water which had been paid for by taxpayers to preserve Australia’s inland rivers.

In its terms of reference, the Royal Commission was to investigate whether the Water Resource Plans set up by the state governments – according to the provisions of the Water Act 2007 and the Murray-Darling Basin Plan 2012 (the Basin Plan) – would be complied with correctly by the deadline of June 30, 2019. It had quite a broad brief to consider.

Among the considerations:

- if there was inadequate compliance, and if not, why not;

- whether the Basin Plan would produce the environmental outcomes and an extra 450GL which was meant to be destined for South Australia and if not, why not;

- what was necessary to achieve this;

- what the likely impacts of non-compliance were;

- what enforcement proceedings had taken place in respect of illegal takes of water;

- whether enforcement and compliance provisions under the Water Act were adequate;

- whether the modelling was adequate to the task;

- and whether the Basin Plan and its implementation were adequate to achieve the objectives and purposes demanded by the Water Act and Basin Plan, taking into account climate change.

The report of the Royal Commission is expected in early February. Based on the evidence presented so far from submissions, hearings and the Issues Paper II, we can expect the Commission to find that the Murray-Darling Basin Authority (the Basin Authority) has acted in a manner inconsistent with the Water Act 2007 , which is the enabling Commonwealth legislation for both the Basin Authority and the Basin Plan it produced.

The Commissioner is also likely to find that the implementation of the plan has been marred by maladministration on the part of both the Authority’ executive and its board. Huge amounts of money have been spent by the Commonwealth, but the Basin Authority has lacked transparency and accountability, and has been found to have engaged in subterfuge and deceit.

The end result, according to Counsel Assisting, Richard Beasley SC, has effectively been “a fraud on the environment.”

How did it get to this?

Act Two: The Farce

Conflict over governance of water resources has a long and inglorious history in this country, going all the way back to Federation. However, the enactment of the Water Act 2007 marked a critical point in the establishment of a national governance structure. The Water Act recognised that too much water was being taken from the Murray-Darling Basin and it sought to reset the balance between environmental and human use of water, in order to establish long-term sustainable water use in the Basin.

It does this by determining the environmentally sustainable level of water “take” (ESLT), which is the volume of water to be diverted for consumptive use, a volume which cannot compromise key environmental assets, key ecosystems functions, the productive base of water resources, or key environmental outcomes.

The Water Act therefore sets a volume for human consumption, the sustainable diversion limit (Sustainable Diversion Limits), and puts processes and timelines in place to achieve this. The management arrangements established in the plan are supposed to be established by the Basin states by June 30, 2019, and the activities to reset the balance between the environment and human consumptive uses are supposed to be fully implemented by June 2024.

In order to comply with Australia’s international environmental commitments, particularly the RAMSAR treaty, (bearing in mind that the external affairs power of the Constitution is one of the two heads of power relied on by the Commonwealth to enact this legislation), the Water Act requires that the Murray-Darling Basin Plan be based on the best available science, with due attention to the effects of climate change. The ecological needs of the river system are to be paramount.

“scientific best evidence was ignored, subverted or altered to secure predetermined political outcomes”

Instead, the Royal Commission heard scientific best evidence has been ignored, subverted or altered to secure predetermined political outcomes.

Moreover, the Commission heard facts and reports were “trimmed” for political expediency. A culture was rapidly established of deception, secrecy, censorship, and the political fix. The modelling on which the Murray-Darling Basin Plan was based was not produced, seven years later.

The science which the Basin Authority purported to rely on was considered by scientists as “not science”. Scientists were leaned on. Work that was relied on was not peer reviewed, reports were changed against the wishes of the authors, scientists and experts were pressured.

The current “Sustainable Diversion Limit” (SDL) did not reflect an environmentally sustainable level of “take”. The Commission heard there was even evidence to suggest knowing or reckless disobedience of the law on the part of the Murray-Darling Basin Authority. The Basin Authority also failed to engage with climate science in any meaningful way.

As David Bell, a former employee of the Basin Authority from 2009-2017 noted to the Royal Commission,

“Somewhere [in 2011] there was a change in understanding about what the Water Act required the Murray-Darling Basin Authority to do.”

This change appeared to have little to do with good administration or with the application of scientific best knowledge to a public policy issue, and everything to do with politics.

Bret Walker SC

Observers described the evidence presented at the Royal Commission as nothing short of stunning. The Commissioner, Bret Walker S.C, an eminent constitutional and administrative law expert, gave interested parties and stakeholders opportunity for due process, with repeated and ample warnings to address the evidence in the interests of procedural fairness.

While there was extensive and detailed evidence from eminent water experts, environmentalists and irrigator groups, neither the Basin Authority, the Eastern seaboard states, nor the Commonwealth and its bureaucrats had answers to give to any of the evidence, and there were no challenges to the factual or expert evidence.

However, they did go to farcical lengths to prevent any of their staff from speaking to the Commissioner. The Commissioner invited the Commonwealth government, the Basin Authority, and the basin state governments to appear at a public hearing, and all basin states made submissions. However, the states declined to give evidence to the commission, and they declined to answer any of the questions put by the Commissioner. Counsel Assisting Richard Beasley S.C (a noted specialist in environmental law) noted in his summing up for the Commissioner that the submissions from state governments were

“..either totally unhelpful or not particularly helpful.”

The Basin Authority and the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources provided submissions which did not really address the terms of reference or key factual matters raised. The Basin Authority actually sent the Commissioner a letter saying they were too busy to meet. Beasley noted that this standard of behaviour was

“a very poor and surprising means of interacting with a Royal Commission”.

This is too much. This #LNP government has taken #coverup to a whole new level. How much are they trying to hide?#Water #corruption #auspol#BarnabyJoyce

High court asked to block SA royal commission from calling witnesseshttps://t.co/NAwp8umxNi

— Mike ?????️?? (@HikaEbop) June 13, 2018

The Commissioner’s attempt to compel Commonwealth witnesses to appear was even met with a challenge by the Federal government and the Basin Authority in the High Court, seeking an injunction on constitutional grounds and resulting in a remarkable stoush between the Commissioner and the current Minister for Agriculture and Water Resources David Littleproud.

Littleproud’s High Court headache went away when the case was dropped – after the South Australian Liberal government’s initial enthusiasm for the commission suddenly cooled when it won office. Attorney General Vickie Chapman refused to grant the commission an extension of time, and became involved in an extraordinary barney with Commissioner Bret Walker after issuing a media release misreporting him, causing the Commissioner to demand an apology.

This bizarre behaviour by public authorities led Beasley to remark drily in his summing up that,

“Presumably, issues relating to the proper management of Australia’s water resources should be equated to State secrets.”

In the end, a veritable Who’s Who of pre-eminent water experts, bureaucrats and academics provided a great deal of useful information which was garnered by the Royal Commission; but no one who was a current serving member of a statutory or governmental authority appeared, except from South Australia.

Interval: an explainer for civilians

The key feature for resetting the balance between “environmental” water and water for human consumption is the recovery of environmental water in order to achieve a Sustainable Diversion Limit (SDL).

In 2012, the Murray-Darling Basin Authority published the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, which established that 2750 GL of water for consumptive use be recovered as environmental water by 30 June 2019, with an extra 450GL to be recovered outside of the Basin Plan, to appease South Australia.

To do this, the federal government was buying back water entitlements — the so-called “water buybacks”, and invested in infrastructure efficiency measures, on and off-farm and the river. The Australian government set aside $13 billion to implement the plan via its various activities (water buybacks; irrigation infrastructure, and various supply measures, such as the removal of constraints, which impede or misdirect water flow), but the responsibility for practical implementation of measures lies with the Basin states, via their own “Water Resource Plans”, which must implement the outlines of the Act and the Basin Plan.

The states are ultimately responsible for compliance of their water take laws with the Basin Plan and Water Act. The Basin Authority, as the regulator and provider of key support for the state governments, is the key Commonwealth actor.

In addition, a Commonwealth program for enhanced water flows for South Australia was added as a note to the Basin plan legislation. It provided Commonwealth funds for the implementation of “efficiency measures” (reducing water losses via infrastructure improvements) amounting to the recovery of the equivalent of 450 GL of environmental water.

Crucial to the proper interpretation of the Water Act is the recognition that the environment cannot be compromised, and social-economic factors play no part in the derivation of the SDL.

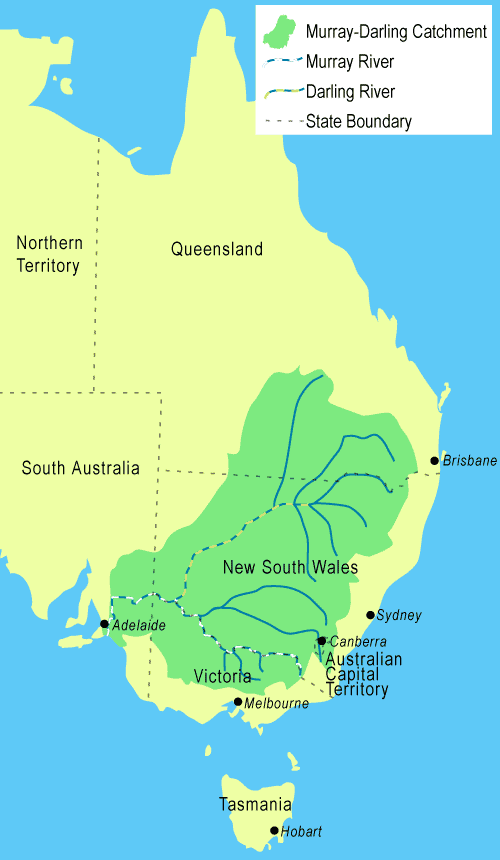

Murray catchment map MJCO2

Act three: the tragedy

Where did it all go wrong?

In October 2010, as part of the preparation of the Basin Plan, the Basin Authority produced a report entitled “Guide to the Proposed Basin Plan”. This was merely a discussion paper that put the figure needed of water recovered for the environment at between 3856 and 6983 GL – but note, this lower figure had a “high uncertainty” of achieving its environmental objectives.

The report caused a wave of outrage and angst. In Deniliquin and Griffith, angry crowds burned copies of the report in the street. Great pressure was brought to bear on the Labor Minister for Agriculture at the time, Tony Burke; and a parliamentary inquiry chaired by Tony Windsor rebuked the Basin Authority.

At some point after this, coinciding with the appointment of a new chair of the board, the Basin Authority seems to have buckled. Despite the fact that recovery of 3856 GL for the environment had been determined to represent a “high uncertainty” of achieving environmental objectives, evidence to the Royal Commission strongly suggests that a decision had been made to reduce the amount of environmental water to be recovered even below this level in order to get the eastern states to sign onto the Basin Plan.

As Bell put it,

“At some point, there was a very clear understanding that [the volume of environmental water recovery] had to be beginning with a number two.”

Evidence presented to the Royal Commission indicates there is little chance to secure ecological outcomes for the river system with this level of environmental water recovery. Further, Bell notes that after the Basin Plan was enacted,

“there were ongoing attempts to water down its requirements.”

This dynamic was exacerbated by Barnaby Joyce during his time as Water Resources Minister, when he doubled down on the rhetoric of the “triple bottom line”, effectively inverting the concept so that economic and social needs took precedence over environmental, subverting the intention of the Water Act.

Counsel Assisting Beasley described this as a public relations sound-bite made up by the Basin Authority. There can be no trade-offs between environmental objectives and socio-economic ones, as the environmental objectives of the Act are subordinate to Australia’s international environmental treaty obligations.

So, initial findings suggest the environmental outcomes are not going to materialise, and neither is the 450GL extra water for South Australia. The former Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder David Papps put it like this:

“I bet my house that South Australia will not get the 450GL” .

But it gets worse. The role of Barnaby Joyce in “tilting” the Basin Authority towards irrigators has been publicly noted, including by the Basin Authority’s own advisory committee. Critics say this “tilting” has benefitted some irrigators, but undermined environmental outcomes and wasted public money.

After Barnaby Joyce became Water Resources Minister in 2015, he cancelled government water buyback, effectively only allowing environmental water recovery through the mechanism of infrastructure subsidies. Many irrigators hate buyback, because they believe it hurts basin communities, but they love infrastructure subsidies, which is essentially free money.

Whistle blower says water theft was known about in the Murray Darling Basin Authority a long time before charges were laid @ Barnaby Joyce did nothing or condoned it #auspol https://t.co/VhLT0ipL6L

— Terry Australis (@AustralisTerry) November 28, 2018

However, the Royal Commission did not find any evidence that government buybacks hurt basin communities. This is a conclusion supported by the Productivity Commission, which released its interim Murray-Darling Basin Plan Five Year Assessment report in August 2018.

What is more, the Productivity Commission found that water buybacks were more efficient than infrastructure programs, providing better value for money as well as environmental outcomes. Despite some communities claiming negative outcomes from the buyback programs, this was found to be unlikely by both the Productivity Commission and the Royal Commission.

Other factors (mainly the impacts of the Millennium Drought and industry transformation in agriculture) have been at play to account for the social harms that local communities have reported – but our political leaders have not done a sound job of explaining this to basin communities who are rightfully worried.

The infrastructure efficiency measures emphasised by Barnaby Joyce have in all likelihood resulted in a significant waste of public money. Efficiency measures have been found to be inefficient, inequitable, and what’s worse, not even effective environmentally. One Ernst Young report of 2018 has shown that money has rewarded the inefficient irrigators, who were generously rewarded with efficiency supply measure projects, while efficient irrigators have not been impressed.

The institutional failures are many and notable. Across the board, there has been a lack of transparency and an excess of secrecy. The Productivity Commission noted for example that the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (DAWR) does not have a systematic and transparent process to demonstrate that recovered water has environmental value.

This means that the impact of water efficiency measures are unknown. Furthermore, the Productivity Commission notes, the effectiveness of water buybacks were not always known either. Water buybacks made by direct negotiation were not systematically released and the DAWR paid “a substantial premium above market prices to recover water through infrastructure modernisation”. The Department did not undertake a comprehensive assessment of costs and benefits of this.

As for the Basin Authority, the Productivity Commission found that the Basin Authority “is an inherently conflicted entity and is perceived as such by stakeholders”, and this inherent conflict will be exacerbated over the next five years. Its ability to be an impartial regulator is compromised by the fact it also operates as an advisor to Basin states, and provides them with technical support. Its independence from political pressure is also suspect.

Epilogue

While the main actors in this play are the Murray-Darling Basin Authority and Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, the subtext is the stench of influence-peddling, cronyism, regulatory capture, conflicts of interest and political bad faith that plagues all levels of Australian politics. There are legitimate questions about who and what our political parties and our bureaucrats have been representing and defending.

About this, much can and will be written in coming months. So, this epilogue is really… the prologue.

*The Royal Commission Report is due in early February 2019, and the Productivity Commission was due in December 2018 and must be tabled publicly early in 2019.

———————-

The above investigation is published anonymously at the author’s request. “Triskele’s” identity and bona fides are known to us. “Triskele”  is an academic and journal editor as well as independent researcher interested in politics, history, current affairs, books, languages, and “all things nerdy”.

is an academic and journal editor as well as independent researcher interested in politics, history, current affairs, books, languages, and “all things nerdy”.

Public support is vital so this website can continue to fund investigations and publish stories which speak truth to power. Please subscribe for the free newsletter, share stories on social media and, if you can afford it, tip in $5 a month.

The above investigation is published anonymously at the author’s request. Triskele’s identity and bona fides are known to us. Triskele is an academic and journal editor as well as independent researcher interested in politics, history, current affairs, books, languages, and “all things nerdy”.