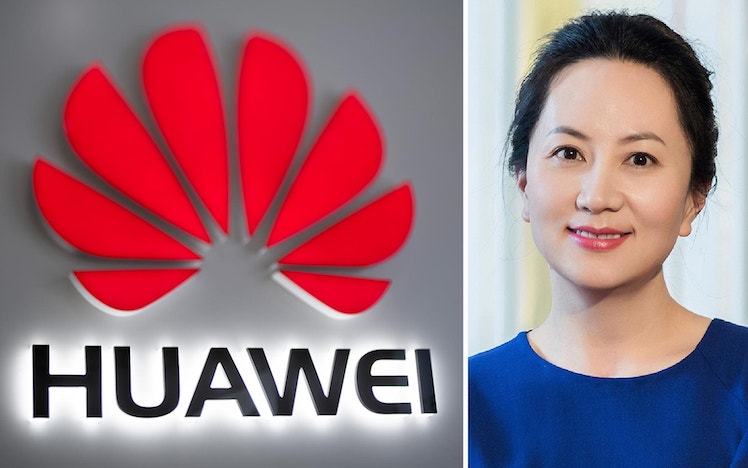

The arrest of Huawei’s Meng Wanzhou may restart the US-China trade war, but it will just be a headwind of the looming global financial crash. Michael Sainsbury reports.

YOU WOULD not want to be a Canadian, or perhaps an American in China right now. In recent days, the Chinese Communist Party has detained two Canadians out of the blue for reasons of “national security” in retribution for its government detention of Meng Wanzhou, the CFO of China’s most successful international company, Huawei Technologies.

It is just the latest example of China’s capriciousness and complete disregard for any rules or deals when it feels like it and should be taken by every businessperson with yuan signs in their eyes as they look towards the Middle Kingdom, to think twice.

Meng, who used to go by the English name Cathy but dumped it in favour of the sexier Sabrina, was arrested in Vancouver at the request of the US government, who wishes to extradite her. She is in on bail in one of a multi-million dollar mansions she and her husband own in Vancouver which has, in recent years, turned into something of a satellite city for wealthy Southern Chinese.

It’s an event that is already unsettling global markets at a time when fears for the health of the economies of both the US and China — and thus the rest of the world — are rising quickly.

It was all supposed to be different. Or was it? About the time Meng was taken into custody, as she changed planes at Vancouver airport, Donald Trump and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping were sitting down to a dinner at the recent G20 summit in Buenos Aires. Trump’s plan was to call a temporary truce to the imposition of tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars of Chinese goods by the US — and some tit for tat from China. The announcement of this has been overtaken by the arrest.

The arrest of a former Canadian diplomat in China and unexpected comments from President Trump raise a fresh question about the case of Huawei's Meng Wanzhou: How political is it? https://t.co/LCSCnjXneV

— WSJ China Real Time (@ChinaRealTime) December 13, 2018

The accusations against her and Huawei relate to the breaking of sanctions against Iran, and lying to international banks about Huawei’s control over a subsidiary it now seems is co-owned by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard. The alleged crimes reportedly carry prison terms of 30 years.

US officials have claimed that Meng’s arrest and the accusations against Huawei have nothing to do with the US-Chinese trade war, but that’s hard to believe. Global securities markets have reacted by falling sharply.

The core of the US-China stoush, for all the sound and fury, is about intellectual property theft and transference in the tech sector. Huawei and its Chinese competitors have long been front and centre of this trend. Indeed, more than a decade ago, Huawei was taken to court over allegations of IP theft from Cisco Systems.

To add further confusion, US National Security Adviser John Bolton has admitted that he knew of Meng’s arrest warrant ahead of its execution, yet claims that he was unsure if Trump knew as he met Xi. If that’s true, it’s incompetence; if it’s not, then it’s even more lies from the White House.

The accusations against Huawei are similar to those made against its smaller Chinese competitor, ZTE Technologies, which almost sent it bankrupt in 2017-18.

Meng’s arrest also comes as the US has stepped up pressure on its allies to ban Huawei from major telecoms infrastructure contracts and, indeed, to have its gear ripped out on cyber security grounds. Australia has played along faithfully with the US, banning Huawei from the benighted National Broadband Network and from emerging 5G networks.

Turnbull’s pro-China lovefest another casualty as Huawei gets the flick

In recent weeks, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and Japan have all slapped bans on Huawei in their own broadband networks.

China has reacted with typical fury – senior Huawei executives are widely said to be in Xi’s inner circle – describing the arrest as “unreasonable and vile”. While Meng’s arrest has short-circuited Trump’s triumph at taking a break in a trade war he started, it’s too early to understand if the Huawei move is a ploy ahead of the main game that Trump will recommence at the end of February.

To add some more confusion Trump has said he may step in to the standoff to save his “biggest ever”trade deal with China.

Of more concern for the global economy, and Australia in particular, is that the trade war is only one of many headwinds now buffeting China’s economy, which exhibited further signs of being in trouble. Decelerating inflation and fading domestic demand were evident in figures released latest weekend — a major stoush between Huawei and Washington can only exacerbate.

Crucially for Australia, the Chinese economy – about 28 per cent of two-way trade and 33 per cent of export revenues – is now inextricably entwined with the world economy, meaning an economic hit to China could have double impact.

China’s economy has been slowing for some years back, from low double digits towards six per cent; something of a designated bottom-of-the-floor number for Beijing.

Still, this is off an increasing base, so even as growth slows, the quantum of exports often increases. A running series of infrastructure-based stimuli over past decades has brought ever-decreasing returns on investment.

Ultimately there is a limit to how many highways to nowhere and ever-empty airports can be built, adding to the debt and other dead weight. The state balance sheet has reached levels that increasing numbers of economists believe is dangerous.

Lower infrastructure spend is bad news for Australia’s resources sector and commodities prices are already bearing the brunt, signaling a crimping in mining-sector tax receipts in coming years for the government. But the ebbing global economic tide will strand many ships.

Chinese debt is getting very heady, close to 300 per cent of GDP, and could be the trigger for the next wave of what is looking like a multi-decade global financial crisis. The US economy shows all the signs of having peaked and the international economy is now in year 10 of growth in an era where cycles average eight years. Gravity eventually prevails.

Perhaps the richest irony of all is that this has all come as China is gearing up, this month, to celebrate 40 years since Deng Xiaoping commenced his storied program of economic reform.

Since Xi took charge, despite a laundry list of reform promises, the Chinese economy had become more not less open. Beijing run state owned enterprises, notoriously inefficient allocators of capital like the government that owns them have become more powerful, building up in recent years and still controlling key sectors of the economy including energy, resources, telecoms and finance.

The Huawei event has seen China offer some concession to the US but, in all likelihood, these were coming down the pipe anyway as the WTO countries work to claim the trade war that has been roiling global markets. The US stock markets, for instance, had shed all its gains for 2018 in the past two weeks with December traditional a god month for markets

The impasse over Brexit in the UK and riots across France for the past three weekends – and counting – have only added to gathering fear and uncertainty, UK PM Theresa May and French President Emmanuel Macron have a disturbingly tenuous grip on their economies, the world 5th and 6th largest.

China’s economic woes are already buffeting South East Asia and the regions No 2 and 3 most populated countries and largest democracies India and Indonesia both face elections in April/May which are expected to be bitterly fought, bringing further uncertainty.

Don’t blame flimsy trade war truce – exposed by Huawei arrest – or the Fed for market turbulence. Instead, look to China’s economic woes | South China Morning Post https://t.co/x1qXiwvIqU

— Peter Zeihan (@PeterZeihan) December 11, 2018

Frankly, it’s hard to find any good news right now with the mercurial US President Donald Trump now squarely in the sights of prosecutors and threatening a government shutdown over billions of dollars for his Mexican border wall, all bets are off.

The arrest of Huawei’s Meng may just be the match that lights the fuse for the next round of serious global economic upheaval. Look out below and enjoy Christmas while you can.

Telstra caught in a perfect storm as 5G and the NBN threaten major disruption

Public support is vital so this website can continue to fund investigations and publish stories which speak truth to power. Please subscribe for the free newsletter, share stories on social media and, if you can afford it, tip in $5 a month.

Michael Sainsbury is a former China correspondent who has lived and worked across North, Southeast and South Asia for 11 years. Now based in regional Australia, he has more than 25 years’ experience writing about business, politics and human rights in Australia and the Indo-Pacific. He has worked for News Corp, Fairfax, Nikkei and a range of independent media outlets and has won multiple awards in Australia and Asia for his reporting. He is a fierce believer in the importance of independent media.