As NSW plunges back into lockdown, the banks have been warned to prepare for negative interest rates. Meanwhile, the Reserve Bank has quietly conceded the banks have not lent the $188 billion pandemic stimulus, instead parking it in their $314b war-chest at the central bank earning no interest. Michael West on looming storm-clouds.

It will have gone largely unnoticed, very largely unnoticed, but the banks have been warned to prepare for negative interest rates. Negative rates mean you pay the bank to park your money, rather than the bank paying interest to you, the depositor.

It’s a radical proposition, something never before seen in this country, and something the Reserve Bank has said would not happen.

When money is this cheap, it is not good. Negative interest rates presage a listless economy, and storm clouds are massing on the economic horizon as the Sydney lockdown, along with the failure of the federal government’s vaccine roll-out, shackle economic growth around Australia.

The warning to prepare for negative rates has come via a letter from the prudential regulator APRA; and it reflects a world in flux and renewed uncertainty in Australia. This week’s inflation figures in the US showed an extraordinary 5.4% rise, while, here in Australia, optimism over the incipient post-Covid recovery is being smothered by the NSW outbreak.

Meanwhile, another strange thing happened. Highly regarded central bank governor Guy Debelle made an unusually frank, although furtive admission. Buried in some footnotes to a speech in May, Debelle conceded that the major stimulus initiative of the pandemic, the TFF (Term Funding Facility), had failed.

Here are the interesting bits:

“There are a lot of banks with large ES balances who are willing to lend them.”

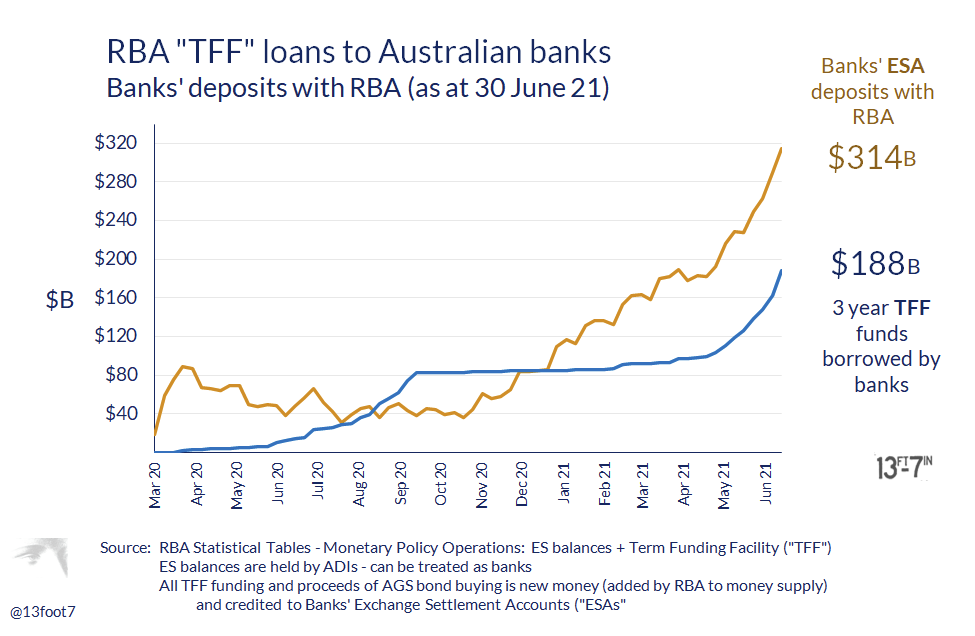

Debelle is referring to the fact that the banks have $314b sitting in Exchange Settlement Accounts with the central bank.

Some $188b of this is TFF money, money created by the RBA for the banks, money whose purpose was to be lent by the banks to businesses in order to stimulate the economy.

Debelle’s second interesting point, and a point which goes to the integrity of the central bank and its leadership, is an admission that it has been the RBA’s fault.

“The large amounts of deposits is a direct consequence of the policy actions.”

To paraphrase Debelle: “we thought it would work, we thought the banks would lend it. It was our idea but, heh, it didn’t work; the banks didn’t lend it, they just parked it back with us on deposit”.

Now Debelle, along with his boss Phillip Lowe and the central bank crew, have to work out what to do about this $314 billion.

The TFF part of it is a loan, albeit a very low interest loan. So, on June 30, 2024, the commercial banks have to repay the $188b the RBA has lent them.

It was part of the big pandemic stimulus package announced last March when Australia was gripped by the virus. In coordination with the US Federal Reserve, our central bank dropped the cash rate to 0.1%, set up the TFF, thereby creating new money for the banks to lend to small businesses; and began pushing down the interest rate on three year bonds to 0.1% to stimulate the housing market.

The housing bit of the stimulus was just dandy. In fact, the RBA recently moved to dampen the mortgage market by taking its foot off three year rates (the banks borrow to finance home mortgages by issuing three-year bonds).

So, while the TFF is dirt cheap money, it is still a loan (unlike the rest of the money on deposit which is new money created by QE, that is the money the banks got from selling bonds to the RBA). They, the banks, are paying 0.1pc on that 188b parked with the RBA.

In theory, the RBA’s idea was sound. The cheap loans would help the banks keep the pandemic economy afloat.

Here’s how much is in the ESAs on the last day the banks could borrow, two weeks ago on June 30 ($314B, including money the banks also got from selling bonds to the RBA). You can also see how much the banks have borrowed from the RBA ($188B).

But where is the money going to come from to repay the TFF in 2024?

Surely, the banks would have to go to the market and refinance those loans, maybe at new high 2024 interest rates. Not a good outcome.

Guy Debelle: “There is little the banking system can do to reduce these deposits”. Really? That sounds bad too. The RBA governor is saying there is little they can do to force the banks to take the money out, if they don’t want to.

Why aren’t the banks lending the TFF money? They are paying interest, albeit tiny, but prefer to park it in ESAs. Is it because there are not enough good borrowers (apart from the property market of course, where credit has been going berserk)? As Debelle says: “There are a lot of banks with large ES balances who are willing to lend them.”

He goes on, “ES balances are going to remain at a high level for quite a number of years until the funds provided to the banking system under the TFF are repaid [June 2024] and until the government bonds the RBA has bought mature”.

These are bonds which the banks sell to the RBA every Monday Wednesday and Thursday. It would appear a fair chance that the RBA is also going to sell some of its bonds back to the banks at the last minute and soak up what’s left in the ESAs after the $188B loans are paid off.

So the new money which the RBA has created to help us out of the pandemic is still there, sitting in the ESAs. It sits there for three years because the banks won’t use it. The banks give the new money back – as well as using new money to pay interest on the TFF loans.

And so the newly printed money disappears from the system.

Fears that the new money might create inflation are assuaged as the new money has been extracted from the banking system.

Was there ever a point? Well there was; it just never quite happened. Instead the commercial banks can now use their enormous ESA deposits (technically loans from them to the RBA) as a bargaining tool when they borrow offshore to finance the property market and so forth. They can tell foreign banks, look how much money we have, you will have to lend to us very cheaply.

RBA lets it rip: are Australia’s home loan rates finally going to rise?

Michael West established Michael West Media in 2016 to focus on journalism of high public interest, particularly the rising power of corporations over democracy. West was formerly a journalist and editor with Fairfax newspapers, a columnist for News Corp and even, once, a stockbroker.