The giant coal port Dalrymple Bay is up for sale. The financial engineering wizards from Brookfield want out. Brookfield’s debt is humungous, and green hydrogen is looming as a mortal threat to coking coal. They can’t offload it to professional investors, so they are now targeting the mums and dads for a float on the ASX, while even angling for a bail-out by the Queensland Government. Michael West reports on one of the trickiest financial juggling acts you will ever see.

We’d “love to hold it forever”, enthused Brookfield chief executive Sam Pollock at a recent meeting of investors.

It begs the question: if it’s so great Sam, then why are you selling it?

The Ontario accountant, now head of an opaque global empire of infrastructure assets, told analysts on a New York conference call last month that Dalrymple Bay delivered strong cash returns; that it was a stable asset.

The asset, the humungous coal port in Queensland which supplies 20% of the world’s seaborne metallurgical coal market, may well be stable. But everything around it is not. According to research obtained by Michael West Media, Brookfield has a dangerously high level of debt and is desperate to get out.

Stories bobbed up in The Australian and Australian Financial Review newspapers again this week about a public float on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX). No doubt, the figures sent to the myriad bankers and financial advisors selling the float of DBCT (Dalrymple Bay Coal Terminal) as it is monikered in market circles, depict a rosy picture.

Yet a report by US financial advisory firm Dalrymple Finance shows Brookfield’s stellar investment to be the result of “asset stripping, excess leverage, deceptive accounting practices and financial management designed to inflate reported IRR (internal rate of return) at the expense of cash returns to investors”.

It’s a big old tricky mess in other words and, despite the cunning window-dressing, there is no escaping the fact that the regulated revenue of Dalrymple Bay has fallen 23% in 10 years while debt at the asset level has shot up 34%. Put simply, Brookfield has been ripping the cash out of this asset like there is no tomorrow, and injecting debt.

Then there is the spectre of the Port becoming a “stranded asset”. Thermal coal is in existential decline thanks to the rise of renewable energy. Albeit coal exports for electricity generation only make up a small part of the Port’s income.

The bulk of the its income comes from coking coal – coal produced for steel production. The longevity outlook is better with coking coal but the latest report from IEEFA’s coal analyst Tim Buckley estimates the commercialisation of green hydrogen for steel-making will happen in the 2030s, not the 2050s as previously thought.

“Brookfield is one of the sharpest renewable energy investors in the world,” says Buckley. “They know this.”

Dumping the asset on yield-hungry investors in the retail market is therefore a smart move.

The sale process

In a surprise development this week, Queensland Treasurer Cameron Dick, announced the state government has an interest. As part of a $500 million “renewables” initiative, said the story published in the AFR, “the Palaszczuk government will also allocate $500 million to the state-owned fund manager, Queensland Investment Corporation, to buy more local assets, including a possible bid for the Dalrymple Bay coal terminal”.

Coinciding with the AFR story came a story in The Australian that Brookfield has hired advisers including Bank of America, HSBC, Citi and Credit Suisse to get the deal away. “A number of other brokers have also been added to the ticket in what many expect is an effort to gain traction with retail investors.

“These include Wilsons, Ord Minnett, Bell Potter and Morgans. It is understood that the four brokers have each been tasked with selling down about $100m worth of shares in the terminal, capitalising on their strong retail networks.”

As one observer noted, “They have every broker in Australia on this deal. They are going to try to get it out as quickly as possible.” As touted in The Australian the yield would be up to an implausible 7%.

Winding back the clock to the call with analysts a couple of months earlier, Brookfield boss Sam Pollock was both ardent in his praise and yet oddly vague when speaking about the sale of Dalrymple Bay.

While Brookfield would “love to hold it forever”, it would sell for the right price. Pollock also noted that management thought the coal terminal’s investment characteristics would “attract the highest valuations”.

“These statements do not comport with reality,” says the Dalrymple Finance report. “The asset has in fact been for sale officially since at least December 2019 when the sales process was first reported in the Australian media. It is unclear why Mr Pollock was obtuse in his references to the sale.”

Perhaps, like many things Brookfield, it has to do with accounting.

Accounting Standard IFRS 5 says that if management is committed to a plan to sell, or initiates an active program to locate a buyer, the asset should be classified as held for sale on the balance sheet. As of the second quarter of 2020, Brookfield had assets held for sale of $39 million and $0 liabilities, which indicates that the coal terminal is not classified properly on Brookfield’s financial statements. Were the terminal classified as held for sale, assets, liabilities and carrying equity would be transparently visible to investors.

Pollock’s enthusiasm for the sale prospects of the terminal is also at odds with reality. It is widely known in Australia that the sales process has not gone smoothly. Initially, the asset was marketed to private buyers. Brookfield has long maintained, correctly, that private valuations were higher than public.

Investment banks collected indicative bids in late February; a week later the roadshow for an IPO began. In mid-March Brookfield put the process on hold citing the pandemic. However, had private bids been close to Brookfield’s asking price, the asset would probably have been sold by now.

Brookfield restarted the process in June via conference calls with its management to gauge institutional interest. Conversations with US funds familiar with the matter indicate the process was “a flop”. Brookfield is now pitching the sale of Dalrymple Bay as a YieldCo in a public offering directed at Australian retail investors.

Australia is a serious profit centre for the Canadian-based asset-jugglers from Brookfield. They took over the construction giant Multiplex many years ago and rolled out a slew of property trusts. Last year, they put their foot on 43 private hospitals via the takeover of Healthscope. These hospitals are now controlled by a Brookfield entity in the Cayman Islands.

It then swooped on nursing home and retirement village operator Aveo, whose business is now controlled by a Brookfield entity in Bermuda.

Such is the pace of the company’s campaign of acquisitions that the asset jugglers have resorted to accounting chicanery to keep the show ticking along. Belligerent tax avoidance is one. Brookfield has been stripping cash out of its Australian assets, Dalrymple Bay among them, for years by loading it up with debt and funnelling the profits to tax havens.

Sam Pollock is sanguine about the stability of DBCT’s earnings (EBITDA) and its cash-flow (Funds from Operations, or FFO). The question is, who gets it?

The accompanying chart shows the Port’s regulated revenue and total cash funnelled up the Brookfield corporate chain to DBCT’s parent.

The amount of cash upstreamed has been very stable for the whole time Brookfield has owned the giant Queensland port, despite the sharp drop in regulated revenue stemming from the regulatory price reset in mid-2016.

The complicated corporate structure of Brookfield means that, were a Brookfield entity to fail, it is unclear how ownership claims would be unravelled. Investors may find themselves with a claim on a ghost asset that vanished in a chain of offshore holding companies.

Spaghetti structure

A glimpse of Brookfield’s structure shows Dalrymple Bay is owned 71% by Brookfield Infrastructure Partners (BIP) and 29% by BIF I. However, neither entity has a direct ownership interest in Dalrymple Bay. Its immediate parent used to be BPIH Pty Ltd, an intermediate holding company and one of Australia’s premier tax cheats.

It is now BPIH Coal Terminal Holdings Pty Ltd. This is likely an interim holding company structure to facilitate sale of DBCT. BPIH Coal Terminal Holdings is likely 100% owned by BPIH Pty Ltd.

Profits from the immediate parent company flow upstream into the black hole of a Bermuda holding company. Capital from BIP and BIF I is amalgamated in the Bermuda holding company, and ownership percentages reported by Brookfield are merely allocations made by accountants on Bay Street in Toronto.

“Brookfield upstreams cash in two ways: as dividends or distributions and from related party loans. Between 2010 and 2019, Brookfield upstreamed $1.023 billion in cash from the port. To the best of our knowledge, Brookfield recorded all cash as distributions received. However, the financial statements of the port terminal show that $544 million (53% of all cash upstreamed) was accounted for as a related party loan,” notes the analysis.

Fake Equity, Fake Income, Real Accounting Problems

This related party loan serves a variety of purposes:

- it creates an asset on the terminal’s financial statements. This is critical as it allowed Brookfield to skirt Australian laws that prohibit the payment of dividends or distributions if the company has or will have negative equity. *

- it allowed Brookfield to artificially inflate the rate of return reported to its private investors.

“The related party loan creates both revenue and an asset on DBCT statements,” says the Dalrymple report. “As DBCT upstreams cash to its parent, an asset builds on its balance sheet; interest charged on the loan is included in DBCT’s top-line revenue figures. The asset and income, in turn, create phantom equity, obscuring asset stripping as it occurs.”

“It is also critical to note that loan is an asset at the DBCT level, but a liability to its owners. BIP and BIF I must repay it prior to selling the asset.

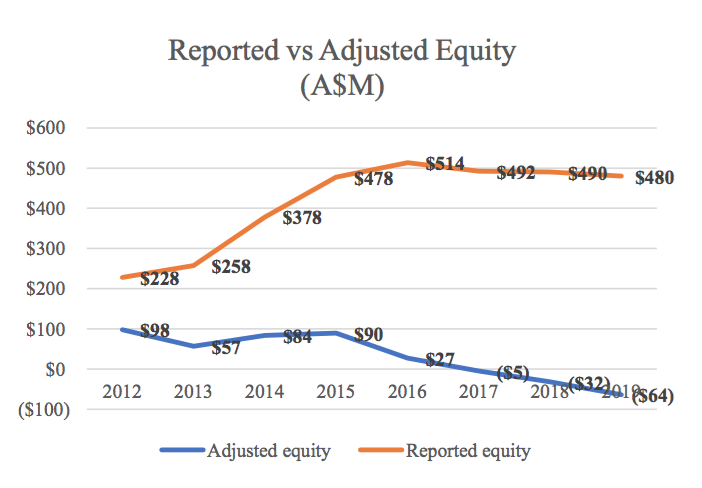

The accompanying chart shows DBCT’s reported total equity and adjusted equity, which assumes all cash upstreamed were distributions and dividends.

Total equity in 2019 was $480 million. If all cash upstreamed was accounted for as dividends, equity would have been negative in 2017, declining further to $64 million in 2019.

Current assets of Dalrymple Bay as reported by Brookfield are the same as those reported by DBCT; total assets of Dalrymple, however, are $213 million less in Canada than are reported in Australia.

“Examination of two accounts shows how the discrepancy is created. Other long-term assets as reported by BIP are ($658m) less than reported in Australia.

Both Brookfield and Dalrymple Bay value the right to use the coal terminal as an intangible asset and it is amortised over the life of the contract. The asset should have the same value on both balance sheets, but it does not.

“Brookfield accountants value the asset on its balance sheet at a 22% premium to Dalrymple Bay’s Australian carrying value. In our view, it looks like accounting manipulation to create equity on Brookfield’s balance sheet and probably the private fund statements as well,” the analysis says.

“Total liabilities reported by BIP were A$127m above DBCT’s reported amount. We believe this reflects the total accrued interest on the loan, which remains on BIP’s balance sheet as debt while the principal balance is eliminated on consolidation.

Capital raising

Private equity firms raise capital from investors largely on their track record. Investors typically measure private equity returns using internal rate of return. Because in 2013, Brookfield closed its second private infrastructure fund, prospective investors at the time would have looked at the returns generated in Brookfield Asset Management’s first fund.

As Brookfield was raising capital, BIF I’s returns were artificially inflated by the use of related party loans.

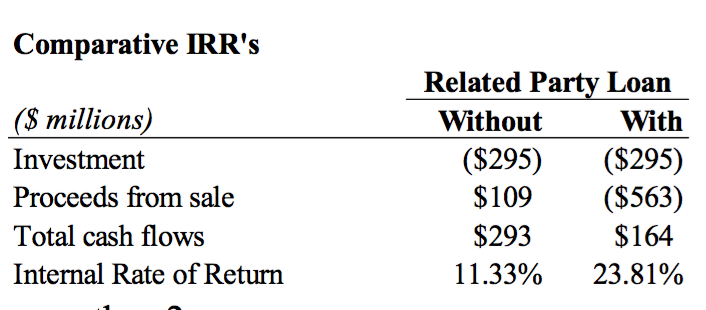

“We assume that DBCT was sold at the end of 2019 for its regulated asset base, approximately $2.5 billion under two scenarios. The first assumes that DBCT only upstreamed dividends – no related party loans. In this scenario, net proceeds from the sale are $109 million. The second scenario assumes Brookfield repaid the related party loan, thus the net proceeds are ($563m).

The accompanying table shows the results. Comparing the IRR for the two scenarios shows the impact of the related party loan. Although the related party loan scenario generates $129m or 43% less cash for investors than the dividend only alternative due to interest expense, the IRR is more than 2x.

Private equity investors pay a good deal of attention to IRR. Brookfield has manipulated Dalrymple Bay’s IRR to pretty-up the beast for market.

IRR calculation is highly sensitive to the timing of cash flows, because it assumes that all cash received is reinvested at the same rate.

Front loading cash flows create an extremely high IRR, which is great for marketing and fundraising, even if it produces significantly lower cash gains for investors, as is the case here. This is borderline lawsuit territory.

“Given that the related party loan seems to benefit Brookfield at the expense of its investors, it could be the basis for a claim of violation of fiduciary duties by an enterprising attorney general of a state in the US with a pension investment,” says the Dalrymple report.

“In September 2010, Brookfield Asset Management gave a presentation to the San Diego County Employees Retirement Association that highlighted the recently purchased Dalrymple Bay. Brookfield said the expected IRR was 19%. Analysis of Brookfield’s financial engineering at Dalrymple Bay indicates why management had such high hopes so early in the investment’s life.”

From the Northern Beaches of Sydney to the Northern Beaches of George Town, Cayman Islands

“Brookfield’s problems selling the coal terminal are not due to the business or investment profile. It is a stable-asset cash flow despite investor concerns with coal exposure. The problem is that Brookfield stripped the asset of future returns leaving it with a crushing amount of debt.”

The accompanying table shows summary financial statements with adjustments from Brookfield’s first year of operation and the last.

Regulated revenue has declined 23% since 2011, reported asset level debt increased 34%, but funds from operations has declined only 11%. As a result, as of 2019, Dalrymple Bay had debt to EBTIDA of 12.6 times and FFO/debt of 5%.

The debt/regulated asset base is approaching 1x. We believe these figures make Dalrymple Bay the most highly levered terminal in Australia.

However, the headline figures both overstate funds from operation and understate debt. FFO should be adjusted to take account of the inexplicable decline in interest expense that occurred following the regulatory price reset in 2016.

“We adjusted the interest expense to reflect what we believe is the real cost, which lowers FFO. We also count the related party loan and an allocation of debt at the BIP level to obtain a total adjusted debt figure.

There are three key factors to consider with evaluating DBCT’s cash flow:

- Current interest expense is inexplicably low. Changes in interest costs over time smooth FFO, but do not reflect changes in interest rates or levels of debt. This has the appearance of “cookie jar” accounting. However, it may be adjustments made to the cost of interest as a result of DBCT’s swap portfolio.

- The debt structure is a problem. Brookfield used bullet maturities for DBCT’s debt. Most YieldCo investors will model in debt amortisation to evaluate the yield. A 25-year amortisation period reduces FFO from a reported $120m to $30-35m.

- Regulated Revenue will likely decline again. DBCT will have another regulatory reset in 2021. If interest rates remain at current levels, cash flows will decline an estimated 20-25%.

The end game

DBCT is an asset which can produce reasonable returns for its financial investors. However, Brookfield was able to take what is an investment with good “real” returns and transform it with manipulative accounting and financial engineering into a great looking investment.

This is the moment of truth for Brookfield. The asset must be sold. Asset level debt of $2.4b approaching 1x its regulated asset basis (RAB) is extremely high considering some Australian infrastructure assets trade at an enterprise value of less than 1x RAB. Further, as DBCT is an out of favour pure-play coal asset and is vulnerable to another cut in regulated revenue due to the current zero interest rate environment, it can be strongly argued that the asset should trade at a discount to its peers.

Perhaps this is why the sales process with institutions has been so arduous – a lot of coal exposure and a lot of debt – leaving Brookfield to resort to inveigling retail investors on the share market.

“Selling DBCT at a price that avoids an impairment charge at DBCT’s owners will be difficult,” notes the Dalrymple report. “Including the related party loan, a $150m allocation of owner level pyramid debt, and BIP’s $140m in reported equity, DBCT needs to fetch an enterprise value of $3.35b or between 1.3x and 1.4x RAB for Brookfield to break-even on the current carrying value.”

A tall order indeed.

Michael West established Michael West Media in 2016 to focus on journalism of high public interest, particularly the rising power of corporations over democracy. West was formerly a journalist and editor with Fairfax newspapers, a columnist for News Corp and even, once, a stockbroker.