Young artists have been disadvantaged by continued cuts in arts funding, with the majority of money going to ‘high-brow’ institutions such as opera, ballet, orchestra which are frequented by older audiences Angad Roy reports on state, Federal and local state-of-play for an arts scene now suddenly devastated by the coronavirus.

Paul Keating once said, “culture and identity… are not distractions from the concerns of ordinary people, their income, their security, mortgage payments and their children’s education and health. Rather, they are an intrinsic part of the way we secure these things.”

Keating is perceived to have seen the Arts as an economic and social essentiality. His landmark ‘Fellowships’ program produced Miles Franklin Award winners, successful theatrical productions, and spurred the careers of creatives such as Jack Davis, John Tranter and Robert Drewe. Moreover, his Creative Nation framework was Australia’s first cultural policy document and internationalised Australian arts. The arts possess wide-ranging ways to perceive the world, to understand ourselves and reason hardship, but that is not the sentiment in politics. Arts are supposed to be understood in relation to their economic value.

In 2016-17, the Bureau of Communications and Arts Research (BCAR) found that culture and creativity activity contributed $111.7 billion dollars to the economy, which equated to 6.4% of GDP. But last year, the Morrison government devolved a standalone federal department with a major focus on the arts. It was rolled into a new entity – the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications. Two questions must then be asked: what value do government’s place on the Arts, and what role do they see it playing in society?

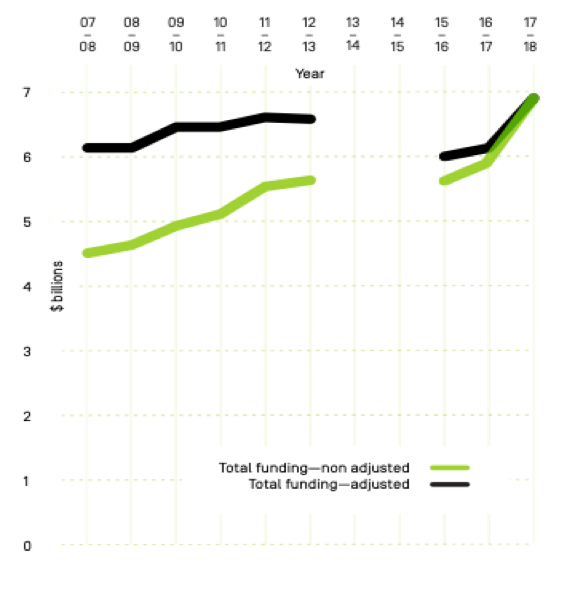

Data collated by A New Approach regarding local, state and federal between 2007-18 provides an insight into the Arts industry both as a funding mechanism and an income generator. Arts funding reached its peak at $6.86 billion in 2017-18 but this funding fluctuated noticeably throughout the decade.

Source: A New Approach

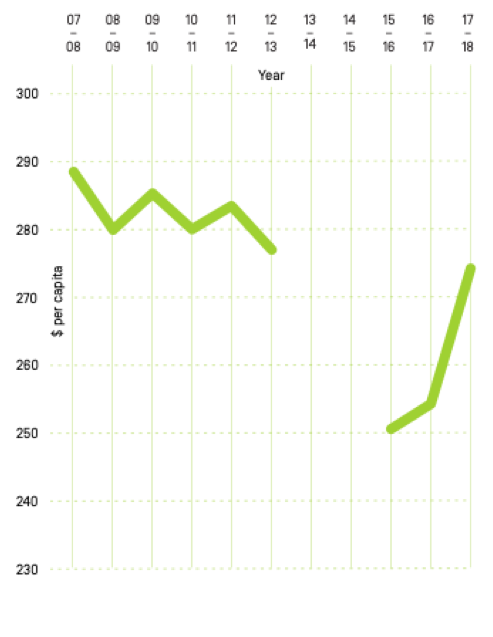

It must be noted that the control of arts funding has experienced a more even split amongst separate local, state and federal powers and on the whole, local and state governments have increased their per capita expenditure by 11% and 3.9% respectively. However, Australia’s population from 2007-18 also increased by 16.9%. In tandem with this growth, total public expenditure on culture stagnated and the chart below conveys a 13% fall over the decade. Expenditure as a percentage of GDP also remained below the OECD average, ranking Australia 26th out of 33 countries.

The Federal Government’s contribution has decreased by 18.9%. The slack picked up, especially by local governments, however, has failed to reconcile population growth and therefore there has been an overall decline in per capita expenditure.

It is important to note that the study recognises an upswing in funding in 2017-18, which is a positive step toward mitigating the gap between per capita expenditure and population growth. One would have predicted a continued trend in this direction, however, successive and unpredictable natural and health disasters (fires, floods, COVID-19) this year are expected to pose significant concerns for an already struggling industry

Already, Canada has budgeted to pay musicians $1000 grants to live stream and New Zealand and Germany have promised significant financial assistance for artists. Meanwhile, in Australia, the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance (MEAA) have said that at least two-thirds of its people are vulnerable as they are casuals or freelancers.

So far, 255,000 events have been cancelled across the country, fielding an estimated income loss of A$280 million. While state and territory governments have announced initiatives to support artists, the Federal government has remained silent.

In NSW, the Berejiklian governments continue to remain obstinate on its plans to spend $1.5 billion relocating part of the Powerhouse Museum to a flooded site in Parramatta. Museums Consultant Kylie Winkworth suggested that 10% of the Powerhouse relocation costs would fund 15 new regional institutions, yet the governments continue to pursue its development plans instead of supporting the broader arts sector.

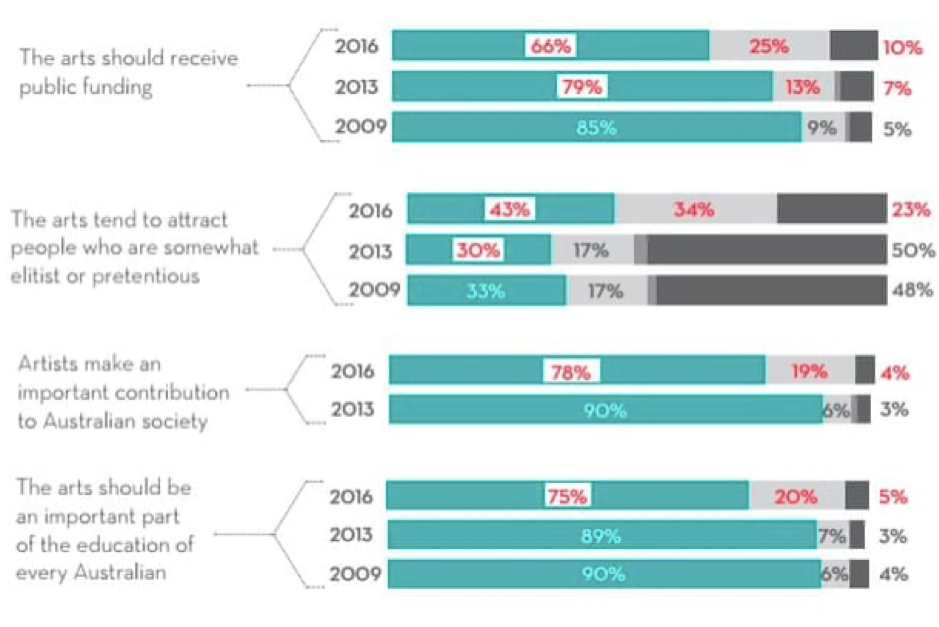

At a federal level, a justification for the inaction on Arts support could be grounded in the Australian Council national arts participation survey.

Photo: Australian Council

Situated within a similar time frame to A New Approach’s report, the survey conveys a public disengagement with the Arts. At a surface level, one can infer that government reductions in spending reflect the overall interests of the population; is this not what a democracy is for? However, if one delves into the allocation of funding, this notion is challenged.

A reason for disengagement is due to the presence of other essential services such as health and infrastructure. When Arts participation is framed as an option of either/or it is natural to favour these. The importance granted to such services – particularly in a period where those from lower demographics are already disproportionately impacted in all major essential services – has a natural flow-on effect to the arts.

This disproportionate impact is evident in the government’s preference toward ‘high’ over ‘low’ art. That is, 62% of the Australian Council for Art’s expenditure goes to the 28 major performing arts companies who engage in the opera, orchestra and major theatre productions. Jarringly, the audience for these events represents around 20% of the population.

Moreover, the Report found that listening to music (97%) and reading books (79%) were two of the most common forms of cultural activity. However, unsurprisingly, over 80% of the Council’s expenditure on musical art forms was allocated to orchestras and the opera. Only 2.7% of funding was allocated to literature.

What remains is a perpetuation of support for the upper classes at the expense of the lower. For artists of any kind, the inability to access funding in a way that can sustain livelihoods has a dramatic impact on the ability to create art.

For decades, art has been used as a sole form of expression to incite change and to challenge power structures. Journalism once had that role but due to successive instances of censorship, most notably, police raids on ABC offices, this role continues to be stifled.

The allocation of arts funding to sectors that only represent a small percentage of the population poses a dire future for small to medium creative companies that form the backbone of the Australian Arts sector, collectively reaching more than 6 million people per year.

This year sees the end of federal funding for 124 of such companies. Real cuts in funding by the Australian Council and the need to re-apply for funding, estimates that there will only be a success rate of 55%-60%. This would mean a shrinkage of the sector by a quarter. Yet, the government brushes over these by leaning on their expenditure at a surface level, with Minister Fletcher justifying this by saying that, “the Australian government spends more than $700m on arts and culture initiatives.”

With the increased likelihood of the disappearance of vital arts organisations and the propping up of high-brow forms, the landscape of Arts in Australia is likely to continue to change dramatically. In 2015, then Arts Minister George Brandis threatened the withdrawal of Commonwealth funding to the Sydney Biennale after artists protested the sponsorship Transfield Holdings, who undertook contract work with an offshore detention centre. This is one example, among many, of how governments continue to position the Arts as a way to favour certain parts of our society.

The future looks bleak for emerging artists and this exists because our politicians commodify the arts. They exercise control over its accessibility and visibility as a tactic to exercise control over the conscience of the society. Reducing the centrality of the arts, the value of the arts to all walks of society, is only another method used by the government to raise a compliant populace that is unable to critique, dissent and shed light on the perpetuation of distributional inequality in society.

Screen Australia board meetings must be a game of musical chairs

Angad Roy is an Honours student at the University of Sydney. He has been previously published in Overland and Honi Soit.