Australia’s welfare system needs a new start. Decades of economic policy decisions have reduced the social welfare safety net for those who are young, working-age – or older without property. The biggest risk of living in poverty in Australia is to receive welfare payments without an additional source of income. Noah Corbett reports.

On March 22, the Government officially announced its second stimulus package in response to COVID-19. The $66 billion package included something that has been ignored for over twenty-five years: a real increase in the payments made to the young and working-age unemployed and students on allowances including Jobseeker (formerly Newstart) and Youth Allowance.

Those on these allowances but not those on the Age Pension will receive a “Coronavirus Supplement” of $550 per fortnight. This has been welcomed by Australians currently receiving government assistance as well as both citizens and businesses who will be impacted by the pandemic.

This temporary measure, which will benefit at least 1 million Australians, throws the inadequacy of the social support network for students and the unemployed into sharp relief.

The previous maximum amount for a single recipient of Jobseeker was $565.70 a fortnight, and for Youth Allowance it was $462.5. The supplement thus effectively doubles of these payments.

This reflects the fact that, in normal times, these allowances are plainly insufficient. At a time when the unemployment rate is projected by the IMF to continue rising to 7.6% in 2020, and 8.9% in 2021, Youth Allowance and Jobseeker will be the sole source of income for an ever-growing group of Australians.

The supplement raises some further questions. Why is it that 55% of those reliant on Jobseeker and 64% of those relying on Youth Allowance are living in relative poverty? Unless there is some more permanent action change, after the end of the coronavirus pandemic, many young and working-age unemployed Australians will go back to living on just $40 a day.

A related question is why the Age Pension been privileged over the government support provided to those who are poor and unemployed in younger generations? This fact is demonstrated starkly by data from the Grattan Institute which shows how the Age Pension manages to keep Pensioners out of relative poverty, whereas other payments do not.

The answer lies in decades of economic policy decisions that have systematically reduced social welfare support for those who are young and of working age but have left the Age Pension largely intact. Most importantly, whilst remaining meagre in terms of the OECD average these policies have benefit wealthy, older Australians who own property and have sizeable superannuation as compared to those, young and old, less fortunate.

These policies have created a future where the young and poor are left behind, while the wealthy simply wait to inherit.

Newstart (now Jobseeker) and Youth Allowance both emerged in the 1990s as part of the Hawke-Keating Government’s reforms to unemployment benefits. The purpose of Newstart was to replace the unemployment benefit with a renewed focus on getting people back into work. Youth Allowance, including both unemployment benefits for those under 22 years, and payments for full-time students and apprentices under 25, had a similar emphasis on ensuring that the young and unemployed in particular were either studying or improving their employability in other ways.

The focus of both payments was to support the young and working-age unemployed and students with some income, but also to incentivise and enable them to seek paid work. This was, perhaps, a necessary change to unemployment benefits in a country where the dole had been designed for a post-war economy with 0.5% unemployment which by 1993 had risen to 8%.

However, at the time of its introduction, Newstart stood at about 90% of the amount paid in the Age Pension, with Youth Allowance providing slightly less. This has fallen to around 60% in the current day (prior to the Coronavirus Supplement).

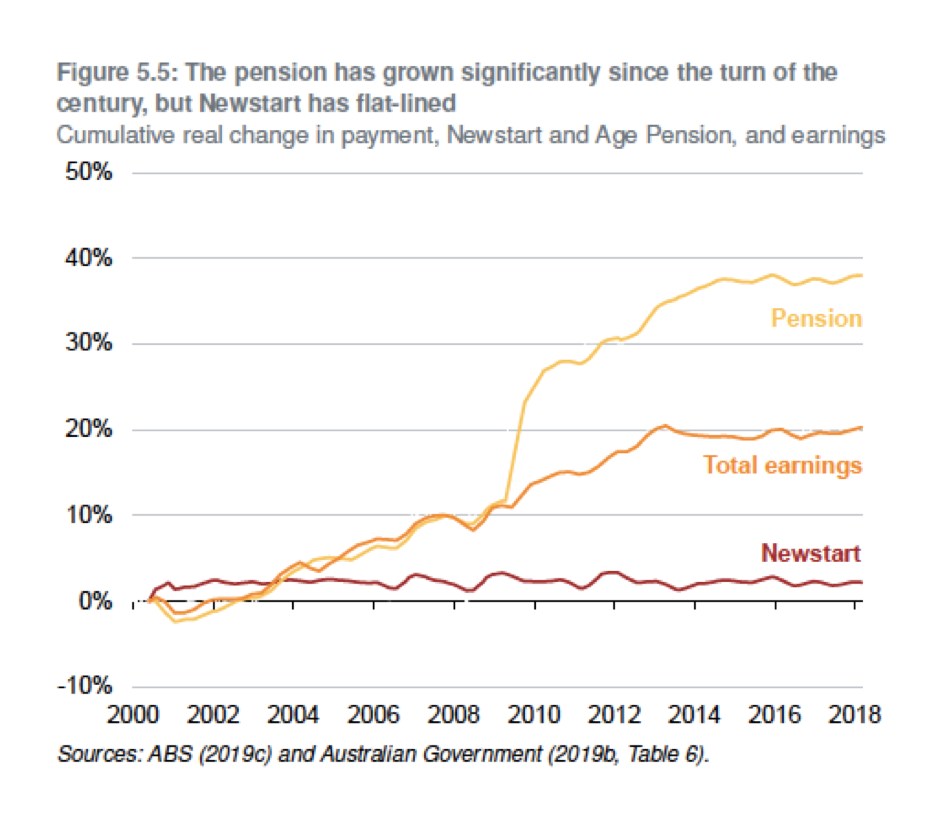

In 1997, the Howard Government made a number of important changes, tying increases in Newstart and Youth Allowance to inflation, as opposed to increases in wages. This change has not been reversed, and in large part explains why the Age Pension has kept pace with wages to keep more pensioners out of relative poverty, whereas payments to the young and unemployed have not.

In addition to this, there was the introduction of so-called “mutual obligation requirements”. In essence, this tied continuing access to payments for unemployed people to engaging in activities such as accredited study, part-time work, Army Reserves, volunteer work, or engaging in “Work for the Dole”. This has reflected the popular “dole-bludger” narrative perpetuated by the media.

In 2006, changes to eligibility requirements for the Disability Support Pension and for parenting payments pushed many young Australians with disabilities, as well as young and unemployed parents, onto Newstart as their sole source of government support. The Gillard Government doubled down on these changes in 2012.

Around 42% of unemployment benefit recipients are now Australians with an illness or a disability preventing them from working full time. Single parents, mostly women, are three times more likely than the average Australian to live below the poverty line.

In 2009, the Rudd Government increased the Age Pension but not Newstart and Youth Allowance. In 2010, the Henry Tax Review found that if that trend continued, by 2040, a single Age Pensioner would receive twice as much as a single unemployed person.

However, there has been no action on the part of successive governments to ensure that the young and working-age unemployed and students are able to live a decent quality of life. In fact, since the Coalition came to power in 2013, it has implemented more stringent mutual obligation requirements, overseen the inaccurate and often cruel Robodebt debt collection scheme (from which Age Pensioners are excluded) and refused to take the advice of successive expert reports showing that these payments are insufficient.

The human consequences of the inadequacy of Newstart and Youth Allowance are stark. 55% of Newstart recipients and 64% of Youth Allowance recipients are living in relative poverty. As the Australian Council of Social Service has noted

‘‘The biggest risk to living in poverty in Australia is to receive Newstart, Youth Allowance or another allowance as your sole source of income.”

This stands in contrast to the Age Pension, which has remained comparatively adequate. Around 2.5 million people, a majority of Australians over 65, receive either a full or partial Age Pension. Half of the government’s total spending on the Age Pension goes to people with more than $500,000 in assets, and more than 40% of Age Pensioners are, in fact, net savers. This is, at least in part, due to the fact that only the first $203,000 of home equity is counted in the assets test, with the remainder ignored.

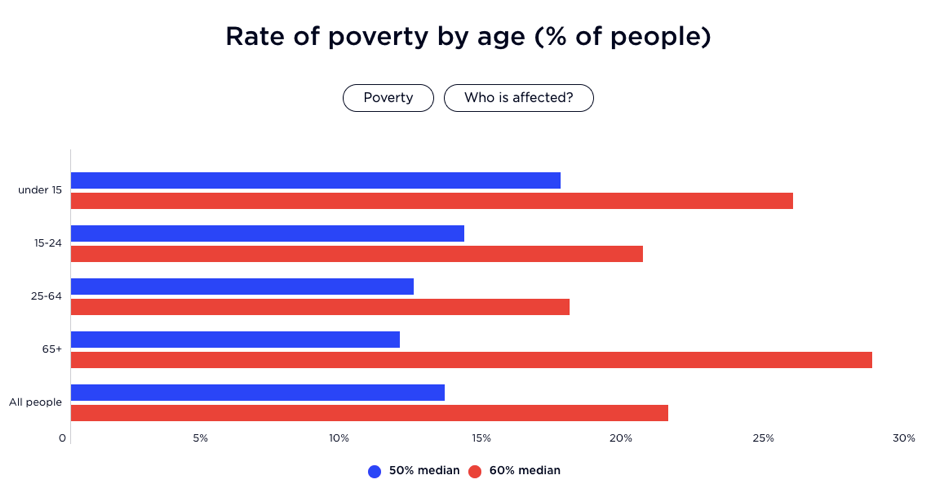

However, poverty amongst pensioners is itself a major issue that must be addressed. Among pensioners who rent, the rate of rental poverty is exceptionally high. While the youth population is proportionally more likely to be below the line of relative poverty if defined at less than 50% of median income, if the bar is raised slightly to 60% of median income, those over the age of 65 tend to be worse off (Australian Council of Social Service). This also disproportionately affects pensioners who do not own their own homes, among whom single women are overrepresented.

What this reflects is that the Age Pension is not generous, and is, arguably, adequate only for those Age Pensioners who own their own homes. It is a minimal and necessary social support for those who are no longer able to work. This minimal support should be expanded for pensioners, but it should also be extended to the younger generations who are unable to work or unable to find work.

This distinction between the Age Pension on the one hand and Youth Allowance and Newstart on the other is both material and political. It is important, however, to note that the Age Pension is not necessarily adequate. Especially for pensioners who rent, there is still a substantial risk of poverty. The Age Pension should be seen as a bare minimum that should be expanded and extended to the younger generations.

Tax Disparity

Among over 65-year olds, only the wealthiest 10% do not receive more benefits from the government than they pay in tax. This means that many wealthy, self-funded retirees are drawing substantially from public funds. Older people pay substantially less in tax, due to a number of tax policy choices (tax-free superannuation income in retirement, refundable franking credits, and special tax offsets for seniors), which mean that an older household with an income of $100,000 a year pays as much tax as a working-age household earning $50,000 a year.

What this means is that students, the working-age unemployed and poorer pensioners are suffering unlike those Baby Boomers who previously earned high incomes, own property and have substantial superannuation savings. This inequality will be transmitted through generations by way of inheritance.

The question for politicians and economic policy decision-makers is ultimately one of priority. After the Coronavirus crisis passes, will we safeguard the savings of wealthy older Australians in order to secure the inheritances of their (generally also older and wealthier) children? Or will we finally review controversial high cost issues like franking credits so that younger Australians who are studying, unemployed, or unable to work by reason of illness or disability can get the bare necessities of a good life? Will we choose, after three decades of neglect, to provide adequate social welfare to our current and future working-age populations?

——————–

Boomers vs Millennials: Federal funding leaves young scientists under pressure

Noah is a fifth year law student at the University of Sydney Law School. In 2019, he completed his Honours in Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney, receiving first class honours and the University Medal. His research focusses on political theory and the contemporary crisis of liberal democracy.