When BHP calls nickel a once in a lifetime investment opportunity, it pays to take notice. At stake is the future of mining in Australia. So, it’s time to learn from history, writes Tosh Szatow. Let’s not squander the next boom, electrification, like the last, a minerals boom whose profits were whisked offshore by a cabal of multinational tax avoiders.

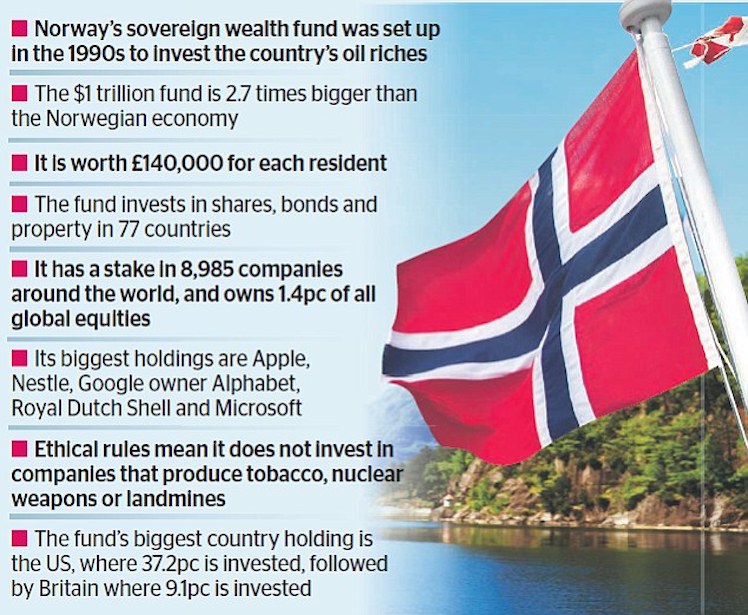

We must learn from the diverging stories of Australia’s squandered iron ore boom, and Norway’s oil-based sovereign wealth success. One of these stories ends with a country endowed with the largest sovereign wealth fund globally, worth approximately four times its citizens’ annual income. The other story ends with a government so cash-strapped it requires celebrity donations to put i-pads in fire trucks.

Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund

With approximately $1,320 of nickel (60kg at $22/kg) in a modern, pure electric vehicle (high nickel battery content is the key to long range and performance), and with the usually conservative International Energy Agency forecasting up to 125m electric vehicles forecast by 2030, the investment opportunity is clear.

The global market for nickel, the key commodity to the “electrify everything” mega-trend that looks set to define transport in the 21st century, could be $165b/pa or more, by 2030. Add lithium, cobalt and graphite to the global battery metal market and you get closer to $250b/pa using today’s depressed battery metal pricing. For context, Australia’s coal exports are worth approximately $65b/pa.

Australia must design a comprehensive framework for direct investment in battery metal supply chains, and passive taxation of the mining industry, to ensure this once in a lifetime investment opportunity benefits all Australians. We must learn from, and build on, the Norway experience. Not only is Australia well endowed with these metals, our global reputation for mining excellence gives us an enormous strategic advantage on this stage.

As demand for nickel and cobalt, in particular, shifts from the relatively anonymous steel and alloy industry to the electric vehicle industry where auto-makers compete hard for consumer loyalty, it will become increasingly difficult for battery makers to hide the ethical and environmental realities of the nickel and cobalt supply chains.

Tesla may have made a vegan car interior, but they find themselves, along with Apple, Google, Microsoft and other big household consumer brands, named in a lawsuit alleging illegal use of child labour in their supply chains. When it comes to cobalt, almost all roads lead to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where the list of alleged corruption abuses is long and risk of labour abuses and conflict minerals is high.

It is no less important, but perhaps less well known, that Indonesia and the Philippines are facing enormous environmental and social challenges around nickel mining. Clearing forests to make way for mining, upstream of human settlements is a bad idea in countries that experience monsoon rain. In response to social and financial pressures, both countries are playing a poker game with customers upstream, threatening to turn off the mining tap unless value-adding occurs domestically, dubbed a rise in resource nationalism. These converging supply chain and sovereign risks combine to make nickel a dicey investment in the archipelagos.

An Australian Sovereign Wealth Fund investing directly in Australian battery metal mining projects fund helps solve three critical, overlapping supply chain problems:

- It brings online reliable supply from a safe jurisdiction, managing brand and reputation risk of electric vehicle makers globally;

- It de-risks private capital investment in the battery metal supply chain, ensuring private capital prioritises Australia as a battery metal mining jurisdiction;

- It overcomes split incentive problems that currently make deal making between auto-makers, battery manufacturers and chemical companies complex and time consuming.

By solving these problems concurrently, an Australian sovereign wealth fund investing directly in mining projects, would position Australia to replicate the success of Norway’s sovereign wealth story. Over time, as supply chains and the electric vehicle industry matures, Australia can balance direct investment with passive taxation strategies, and investment in upstream value-adding, building out a complete battery metal supply ecosystem — this could include running battery recycling facilities globally.

With Tesla now considered an existential threat to every incumbent auto-maker, there is little doubt we are seeing the end of oil as we have known it and the rise of battery metals in its place. The only question is, can we dig i?

————————

https://www.michaelwest.com.au/gas-how-australia-privatised-the-profits-and-socialised-the-losses/

Public support is vital so this website can continue to fund investigations and publish stories which speak truth to power. Please subscribe for the free newsletter, share stories on social media and, if you can afford it, tip in $5 a month.

Tosh works as an independent energy consultant and has been a research scientist with the CSIRO, including overseeing complex inter-disciplinary research on the topic of distributed energy. He would argue that by being an open minded, curious and (arguably) an intelligent non-expert, research suggests he is well placed to reflect on the uncertainty and complexity of the Covid-19 response. Put him in a diverse group of similar people, and he may even make a useful decision when uncertainty is high. Time will tell how true that is.